On a knoll at the northern end of Loch Insh in Badenoch stands a beautiful little white church with a long history and several names. One is the Chapel of the Swans. I first saw the church when our family were visiting the area and pulled up our canoe on the shore below. We walked all around it, peering through the clear windows before discovering to our delight that the door was open and the interior a haven of peace. The north-east window at the front was graced with an engraved Celtic cross based on St John’s Cross from Iona Abbey. Not long after that visit, we moved to the village of Kincraig, joined the congregation and gradually learned more of its fascinating story.

During the Roman occupation of Britain, the peoples living in this area were the Picts. They were one of the Celtic tribes and had a powerful upper class of priests, known as druids. We don’t know for certain what the Celts believed or what form their religious practice took, but there is evidence of both human sacrifice and the use of hilltops for rituals. It is quite probable that where the church sits today was one of their ceremonial sites. But its name, Tom Eunan, points to a later page in its story. In Gaelic, ‘tom’ means ‘mound’ or ‘hillock’ and Eunan or Eònan is the shorter version of Adamnan, so it means: ‘Adamnan’s Mount’.

But who was Adamnan? Born around 625 in Ireland, he came to Scotland as a monk, ultimately becoming the 9th Abbot of Iona. A man of rare scholarship for his time, he wrote the first biography of Columba, the original founder of the Abbey and credited with establishing Christianity in northern Scotland. Written in Latin a century after Columba’s death, Vita Columbae is considered our most important text from early-medieval Scotland, giving not just a protrait of the saint but also of the Picts and the early Gaelic monks. Adamnan died in 704, was made a saint himself and at some point, the church at Insh was dedicated to him and called St Adamnan’s, or St Eunan’s.

Several of the churches in Badenoch, however, including this one, believe their roots could go right back to Columba and his first disciples in the 6th century. A strong tradition holds that the site of Insh Church is one of the few places in Scotland where Christian worship has been held without break since that time. These founding monks often settled on a place of former pagan worship where they built a small stone cell to live in. They used a clearing beside it for gathering the local people to hear their teaching, summoning them with the ringing of a bell. Inside Insh church, there hangs an ancient hand bell that legend maintains belonged to St Adamnan himself. This is unlikely, however, as most bells of the 7th century were iron and this one is bronze. It is possibly a replica of the original and certainly over a thousand years old.

Whatever it lacks in original metal, however, it makes up for in myth. One story holds that not only did Adamnan use it to call the people, but that he also took it down to the shore of Loch Insh to summon the swans to worship. Sure enough, a very old name for the kirk is the Chapel of the Swans. The bell was also believed to have healing power and because of this – the story goes – was stolen and carried to the Scone Palace, where the Scottish kings were crowned on the Stone of Destiny. From the moment it was snatched from the chapel at Insh, however, the tone of its special ring began to change. With a mournful, homesick tolling, it cried out Tom Eònan, Tom Eònan, and no sooner was it set down in Scone, than the magic bell took to the air and flew all the way home again, wailing the whole way.

Unfortunately, its powers of healing did not extend to itself, for when someone dropped it on the old cobble floor of the church it broke, losing a chip and its voice. Legend has it, that if anyone tries to ring the bell, a curse will befall them and a family member will die within the year. For a time, therefore, it was chained up out of reach to prevent such a tragedy. Now it simply hangs on a bar in an alcove of the church under a brace of flame and flanked by doves. Doves are a symbol of peace and of the Holy Spirit – and the Gaelic name for St Columba, was Colmcille, which means ‘the dove’.

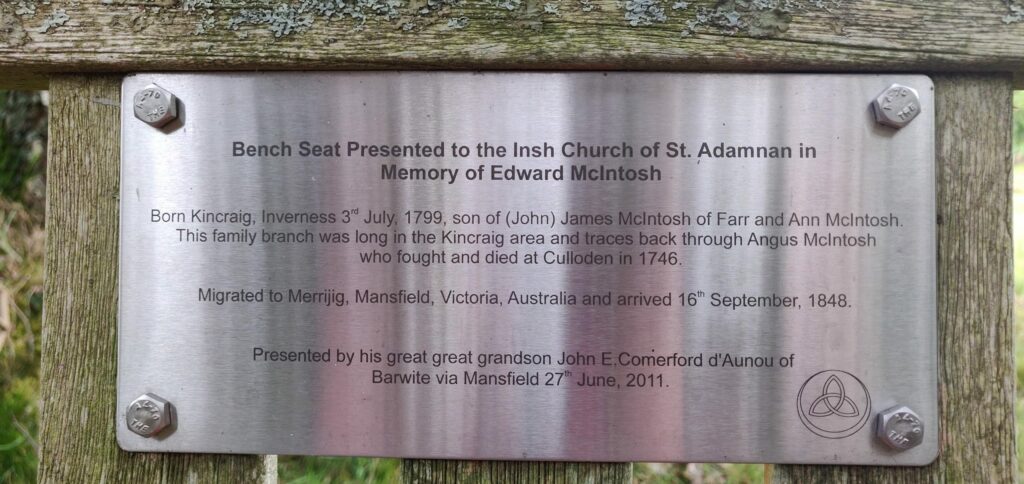

The first written record of the church is in 1190 and the rough stone font in the porch is believed to date from that building. The structure of the building was probably changed several times over the years, but was completely razed and rebuilt in the 1790s as one of the ‘Parliamentary’ churches. Designed by Thomas Telford, these were ordered by the Hanoverian government seeking to suppress Catholic and Jacobean strongholds in the Highlands. The building today dates from then, though significantly remodelled both inside and out.

The old Irish myth of the Swan Children of Lir has also been linked to the church. In the story, the widowed King Lir marries his wicked sister-in-law who is jealous of his four children. Turning them to swans, she banishes them from Ireland, but grants them beautiful voices. They fly across the sea to winter in a faraway land, finding refuge on a loch where they are summoned to worship by a monk’s bell. Loch Insh lays claim to the honour, of course, but not without some basis. Not only do we have Adamnan’s Bell, but this is also one of the chief wintering sites in Scotland of whooper swans. Unlike the mutes, who are here year round, they have a distinctive, mournful cry. You can watch local author and mountain man, Cameron McNeish, tell the whole story here.

Today a Church of Scotland with an active congregation, its common name is Insh Church, Kincraig. It is very special to both locals and visitors, carrying a sense of the sacred in its quiet simplicity. Up until Covid, it was never locked and has always welcomed strangers. One of these, who left his name in the visitors’ book, was John Lennon. Perhaps, for a moment, he imagined there was a heaven.

With its many names and stories, The Chapel of the Swans found its way into my recent novel, Of Stone and Sky, set here in the upper strath of the Spey. Here’s the opening of my chapter Kirk:

It sits on a knoll above the loch, Scots pine rising around it like a company of worshipful giants, waving their arms in the wind, hushing and swishing through the hymns of the sky, leaning quiet to the earth’s prayer. Birch and larch are gathered amongst them, rowan and aspen, oak and yew. A choir of rooks cry out as they beat their silk black robes and circle and roost. Some of the graves in our churchyard are so old the names are lost under lichen, others so new the soil yet lies wounded. To step here is to enter the sacred. It is one of the thin places they say, where the veil between heaven and earth – between spirit and flesh, above and below – is slight as a bee’s wing.

A version of this article first appeared in The Sunday Post. The photographs of me outside and inside the church are by Andrew Cawley. All other photographs are my own.

That Saturday was a night of strange conjuctions in the celestial realm. The Friday before had been the full moon and the Sunday to follow was the vernal equinox. Some call the last full moon of winter the Worm Moon, because of the earthworms that are starting to push up through the soil. This equinox, meanwhile, marks the first day of astronomical spring when the sun crosses the equator from south to north. It is also the moment of equal balance between day and night, the hinge point when winter darkness starts giving way to summer light. Even more special for us, in the Highlands of Scotland, the weather that Saturday was clear and bright.

Alistair and I shoved a tent, sleeping bags, mats, stove and kettle into rucksacks and set off. Our plan was to camp beside the nearby loch to enjoy the huge moon at night and the rising sun in the morning. But as we walked down in the darkness at 8.30 pm I wondered aloud what had happened to the moon. The sky was an inky well, a scattering of stars glinting on its black waters. A strong breeze shivered the trees. No sign of a moon, worm or otherwise.

Native American peoples have different names for this moon. To the Northern Ojibwe it is the Crow Comes Back Moon, because of the bird’s seasonal return, to others the Sugar Moon, because of the sap rising. Right now, to me, it was just the invisible moon and a mystery.

Directly above us, a vast, smooth cloud hung so high it was completely impervious to the wind. Its northern end was black, dissolving into the sky around, but as it reached south its colour softened to grey till the southern-most edges were shining. They looked like curves of foam at the rim of dark waves. And then I realised. Their unearthly glow was from the absent moon. It was still hidden behind the Cairngorm mountains to the south-east, still rising, but already casting its silver light.

The Anglo Saxons called it the Lenten Moon. The name does not derive so much from the Christian period of Lent, but rather the other way around. ‘Lenten’ came from the old English word for ‘lengthening’ of daylight hours and was applied to the religious season. It is followed by the Paschal – or Passover – Moon, and Easter in the western church is the first Sunday after this.

Just as we got to the gate at the lochside, our elusive moon appeared. I don’t remember if I have ever watched a full moon rise before but I do know I have never been so captured by it. As it edged up over the crest of the Feshie hills, this moon was not just full, but vast. And it wasn’t silver, either. It was gold. No photograph can do it justice, but certainly not the ones from my cracked old phone. I also can’t explain the ghostly green satellite above right of the moon. I never saw it in the sky, so perhaps it is a quirk of the camera.

I trained my binoculars on the new-risen moon and took a breath. There were all the familiar craters and crevices and cracks, all those faraway mountains and empty oceans. But there, too, was an extraordinary optical illusion. A rim of flame rippled all around the golden disc. It was as if the sun was not just lending its fierce light but had dipped the moon in petrol and breathed dragon fire across it.

No worm, this moon, but a great, glorious presence, a swelling globe of light against the dark sky. As we rounded the corner of a hill, a powerful wind came whipping across the loch and we had to find a sheltered hollow for the tent. Dumping it, we stretched out on a high bank above to watch the moon glide up the sky like a queen, sending a shining path over the water below her. One old English name for her is the Chaste Moon because of the purity of spring and the denials of lent, but that sounds too pale and deprived for this radiant creature. She was far more the Eagle Moon of the Algonquin people.

When we finally tore ourselves away and crawled into our down bags, sleep was routed by the shaking of the tent and the roaring of the leafless oaks overhead. I understood why the Celts called this the Wind Moon and the Pueblo the Wind Strong Moon. Some folks also named her the Plough Moon, because she marks the time of year to begin turning the fields. This, of course, pulls up those ubiquitous earthworms, and with them, her ugly old name again.

By morning, our Many-Named Moon is gone and the wind with her. In the soft dawn, all is still and quiet, but for the birds. The piping oystercatchers. The dip-diving ducks. A heron. Away on the line of the Feshie hills, not far from the spot the moon rose yesterday, another light is brimming.

It was just before the winter solstice. The day had flung its arms wide for the short hours of light, throwing glitter on every frosted leaf and making the waterways shine. As the sun melted into the south-western hills, the full moon rose directly opposite, like perfectly balanced balls at either end of a cosmic see-saw. The sky around it softened into mauve, smoky blue and turquoise, the silver disc growing bigger and brighter, like a fierce guardian over the depths of winter.

At this darkest, coldest time of the year, it seems a kind of madness to take a canoe onto a Highland loch in the middle of the night. But we did that very thing for the summer solstice, a small party of women in a boat and two paddle boards, on the night that only dims for a few short hours, so it felt right to come back for the year’s counter-weight.

Now we are just three, striking at the irons of winter to set the world turning again. As we embark, thickly swaddled against the cold, our camp kit stowed, we are the Swallow, off for adventure. There is chatter and laughter, a determined tilt to our chins. But our guiding moon is muted now by a thick mist stealing over the world. As we cut across the loch, the black water fades without seam into grey cloud, all the familiar landmarks on the shore dissolving.

Everything falls quiet in this great and shadowy space without bearings. The silence is broken only by the slap of paddles and the creak of boat until unseen geese are startled. Their rising hullabaloo erupts into a storm of wingbeats and splashing near the shore till they circle above us, invisible. Settling again, their cacophany gradually fades into a few disgruntled squawks and then to silence. It is as though they emerged from a formless abyss only to submerge again, more memory now than substance.

We make for the dark island, feeling like the Dawn Treader on the brink of nightmares, at that place in the seas beyond Narnia where dreams come true and nothing could be more terrible. On its shore we judder across a skirt of ice that cracks and splinters beneath us. Now we are the Endurance at the ends of the earth. It is a land we cannot visit from spring to autumn because of a nest that harbours osprey, back from Africa. But we can come now, in winter, to the hallowed ground.

Our vessel hauled up on the frosted shore, we head for a clearing at the foot of giant beeches, sweep away leaves and dig out a circle of turf for a fire. It was the trick of the Highland Travellers, to create a shallow dirt pit for flame and, afterwards, douse it and return the turf, leaving the earth as it was found. Flasks appear, bowls of warm custard on cake and mugs of hot chocolate. There are stories, jokes, memories, hopes. A gathering of women and warmth in the tall forest, on a secret island, in a dark loch, at the heart of winter.

We stretch out under the air without a tent, making our beds in bivvy bags. But I spend the hours trussing myself in ever more layers of fleece, down and discomfort, my body stiffening into cold. On this longest December night, the moon has suffused the fog with a strange half-light and I am as wakeful as when mid-summer will not surrender the sky. It is not a place where dreams come true but where they simply will not come. In the long, freezing hours, I stare at the trees and the embers and the inside of my bivvy bag, finally understand the longing of the watchmen who wait for the morning.

At last it is 7am, still dark but time to move again. Clearing camp by head torch, we discover hair ice pluming from a fallen branch like candy floss. Shiny white and soft to the touch, it is a small miracle of winter that only occurs when the actions of a particular fungus in rotting wood and very precise temperatures come together. The moon is still shrouded and the sun a long way off. An owl makes a wild, demonic shriek from deep in the trees and we depart the forbidden isle.

At first the canoe scrapes across the top of the newly frozen ice before breaking through into water the colour of mercury. Beside us, the reed beds are furred with hoar frost, crackling as we brush past. Cloud holds sway all around, hiding horizons, smudging forest and land, blurring edges. Quietly, we slip back to civilisation, fugitives from another world. In our cargo, the solstice secret, our Promethean fire stolen from the longest night: darkness holds beauty, the cold carves gifts, winter is warmed by friendship.

A shorter version of this article first appeared in the Guardian Country Diary.

Setting up a new event is like taking a running jump off a pier. You don’t know if the water’s going to be freezing, or tangled with seaweed or possibly even infested with sharks. But you just have to do it. Even in time of covid when the complications are multiplied and people are afraid. Especially in time of covid.

And so it was that musician Hamish Napier and myself took the plunge with The Storylands Sessions in September. It’s a new series of events in Badenoch, the lesser-known cousin of Strathspey, higher up the legendary river. Meaning ‘the drowned lands’ in Gaelic, this beautiful floodplain between the Cairngorms and the Monadhliaths is a rich source of stories, from Pictish battles to Jacobite strongholds, the Ossian epic to the Wolf of Badenoch.

It has led to a new name for the area, ‘The Storylands’, in a drive to celebrate its unique heritage. But the stories are not just from the past. Like the Spey, they loop and flow on down the generations, changing course and character as successive peoples come and go, adding new voices and making new stories. So the idea for The Storylands Sessions was born. These are two monthly events in Badenoch, one an open mic focused on storytelling and poetry, with music weaving it all together, and the second a trad tunes session, threaded with stories.

The venue for the open mic is the Loch Insh Watersports centre, so I decided our first theme would be ‘water’ and desperately begged everyone I knew to come and, better still, tell a tale. I was terrified only two-and-half people would turn up and it would feel like slowly setting concrete. But I arrived to a room bright and beautifully arranged by the Loch Insh team and a gradual trickle of people with eager faces.

In our Introduction to Storytelling workshop we started by talking about the common sayings and mottos in our families, like “Waste not want not” or “Blood is thicker than water”. And then we asked: who were the natural raconteurs of our upbringing? The repositories of family history and local legend? There are stories all around us and we tell them all the time, from our explanation for being late to the blow-by-blow account of Auntie Yolanda’s disastrous wedding.

After the workshop, Hamish kicked off the open mic with a bright reel on the whistle called Spey in Spate in celebration of this waterway so prone to flooding. We then listened to Duncan Freshwater’s story of his father Clive’s landmark battle to win access rights on the river in the early days of the Loch Insh watersports centre.

Then the night flowed on through poems about eels, the Spey and The Grey Coast; a comic ballad about an old fisherman, a song about boats and more music on piano, guitar and bazouki. There were hot pies and cold drinks and the stories spilled out: the one from Alice Goodridge, our channel swimmer who was ‘billy no mates’ when she arrived here looking for dookin buddies and has gone on to set up Cairngorm Wild Swimmers and Loch Insh Dippers, with hundreds taking the plunge.

I told the story of The Chapel of the Swans, our ancient church above Loch Insh, with its monks, myths and magical bell. We listened to the tale of a runaway canal barge and a woman’s memories of carrying water to her Irish grandmother’s house. The evening finished with the story from Alistair, my husband and a local GP, of the time in Kathmandu when his unconventional use of ‘Water of Life’ – electrolyte solution – saved a woman’s life. Hamish played us out with his original piano piece, The Dance, and by the end, the place was brimming.

People were talking and laughing – masks and space retained where necessary – but still wallowing happily together in the great wash of good company. Afterwards, when we were packed up, I was exhausted, but high as a kid catapulting off a pier.

Two weeks later, we rode the wave again at The Ghillies Rest bar in the Duke of Gordon Hotel, Kingussie. This time Hamish was master of ceremonies for the Trad Tunes night, and his workshop, A Guide to Folk Sessions, was booked out. With guidance on everything from handling beginners’ nerves to arranging jig medleys, it covered the ABCs of making these mysterious, slippery community gigs work.

Once the music struck up, we had fiddles, whistles, guitars, keyboard, bodhran, a banjo, two harps and a set of small pipes. Keeping everybody in tune and time is no mean feat, but Hamish never once resorted to whacking folks with a shinty stick. He’s saving that for next time. Along with a host of eager amateurs, we were lucky to have top local musicians Ilona Kennedy and Charlie McKerron on fiddles and Sandy MacDonell on pipes. There was even a song, with everyone belting out the chorus of Yellow on the Broom. Together, we lifted the roof.

We have longed for this: to come back together and share our stories, our songs and our lives.

The Storylands Sessions are on every first and fourth Tuesday of the month till February 2022 – and hopefully longer. The second Tuesday of the month is the storytelling event at Loch Insh Boathouse, Kincraig. Our next one is October 12th and the theme is Migration – of wildlife, people, ideas, languages or however you wish to interpret it – so come and share your tale, poem or music! We’re very lucky to have Traveller, author and storyteller, Jess Smith, as our special guest, who will be telling stories and leading a workshop at 7pm on The Natural Voice. Advance booking is essential: click here.

Then, the fourth Tuesday of every month is Hamish’s Trad Tunes session at the Duke of Gordon Hotel, Kingussie. Again, the workshops start at 7 and need to be booked in advance, while the sessions start at 8.30 and are drop-in. For full information and bookings see here. If you’re in the area, come on in – there’s a seat for you.

A shorter version of this article first appeared in The Sunday Post.

We found the abandoned lamb at the edge of a field, bleating plaintively as it trotted towards us on wobbly legs, its mother nowhere in sight. The farmer scooped it up and tossed it into my arms as we climbed back into his four-wheel-drive. The little creature was all soft fleece, wet nose and warm wriggles as it burrowed into my lap, and it reminded me of cuddling baby goats when I was a child in a Nepali village. It also reminded me how much more fun research is than writing.

It was all in a day’s work for me as I developed my recently published novel Of Stone and Sky. It’s the story of a Highland shepherd, Colvin, who disappears and leaves a puzzling trail of his possessions leading up into the Cairngorm mountains. The idea began in the middle of the night one summer, but as soon as I began to write it, I realised I knew precious little about what a shepherd did all day.

This state of affairs had prevailed despite being surrounded by sheep. Where I live in Badenoch, the upper strath of the River Spey, it’s farming country. In fact, the flock from across the road not uncommonly breach their fences and colonise the neighbourhood, even raiding my garden. But apart from the legendary straying of wayward sheep, I didn’t know much about shepherds. Fortunately, several of the ones around me were only too happy to answer my many questions and let me trail around after them like a clue-less lamb.

An unfailingly kind source of information were the Slimon family of Laggan, who – like many locals – have farmed here for several generations. I have rarely been as excited by a literary discovery as when I fell upon Campbell Slimon’s book Stells, Stools, Strupag: A personal reminiscence of sheep, shepherding, farming and the social activities of a Highland Parish. (It’s all pacy, racy thrillers for me!) Even better was meeting Campbell and his wife Sheena and their son Archie and daughter-in-law, Cathy, and learning first-hand what the sheep farming life was like.

On a surprisingly cold day in May, I joined them in their draughty shed to watch the previous year’s lambs being sorted and processed for their various futures. At the juncture of their destiny, Archie heaved them one by one onto a wooden platform and pinned them into place to prevent kicking, while Campbell and Cathy delivered various ministrations. If you’re squeamish, look away now. Out came an enormous syringe for vaccination, a sharp knife for the docking of tails and a nifty tool for castration. The ones staying on the farm were also ‘keeled’ with a daub of blue paint on the bum, and got ‘lug-marks’ cut into their ears, a distinct pattern linked to each farm which dates back, in some cases, for hundreds of years.

In the summer, I watched Cathy clipping, impressed by the deft handling of disgruntled sheep and the speed of the shearing. Farmers here still help each other out, but community clippings are rapidly giving way to hired contractors. The Slimons gave me a copy of a beautiful film by Jill Brown Media of The Clippings in the Laggan valley, one of the last of its kind. It features local families, and the little kids bouncing on the wool bags grew up into teenagers that I taught at Kingussie High School. The first minute of Jill’s film became the opening for my Zoom book launch.

Then on a bright day in September, I went up the hills above Dalwhinnie for a gathering. Puffing my way up the tussocky slope behind Archie, I marvelled at how the slightest word from him had the dogs rippling out and back, as if joined by invisible threads. At the top, he sent me ahead to wait at the first burn while he prised some sheep out of a gully. Unfortunately, the dogs are not so good at rounding up lost writers, so Archie had to come trudging back to find me, at which point I discovered the trickle I had stopped at was not, in fact, The Burn. Whatever it was, the Slimons now call it Merryn’s Burn.

Another September, I met the family again, this time at the Kingussie sheep mart. Although it’s directly across the road from the high school, I’d never really paid it much heed. At one time one of the busiest livestock markets in the Highlands, it is now half an acre of outdoor pens around a low, weather-beaten, wooden building. From the outside, it looks little more than an oversized, round shed, but inside there was a bustling auction in full swing. Wizened farmers in dun-coloured jackets and tweeds leaned over the railings around the edges as bolshy sheep were herded into the ring, bid for and bought, and herded out the other side. Here was a whole industry, a whole way of life, a whole world, happening right under my nose that I’d never known about.

Learning something of its story and characters was one of the great joys of writing Of Stone and Sky. The account of sheep in Scotland is complicated and fraught with divergent perspectives. When I began writing – knowing from the beginning it was a story about the land as much as the people – I walked in blissful ignorance where angels fear to tread. Now that I know more, I acknowledge the difficulties but also realise that, perhaps, that is what the book has been about all along. It is the story of struggle, of relationships with the land that are as much wrestling as embrace, and of a people forever marked by it. Early in the novel, my shepherd Colvin’s mother, who grew up a Highland Traveller, learns the sheep farming life from her father-in-law. My own learning is captured through her eyes.

“She witnessed his bond. To the sheep and the dogs and the land, to the seasons and the weather, to the neighbouring shepherds in time of need, but mainly to this solitary walk; this ancient herding windblown way.”

Of Stone and Sky is available in hardback and ebook wherever you get your books. You are warmly invited to an evening called The Shepherd’s Tale at the Badenoch Heritage Festival at 7.30 on Friday 24th September in Kingussie. Exploing the many ways the sheep farming story is told, it will include readings from the novel, conversation with the Slimons and Jill Brown, along with a showing of her Blaragie Clippings film and live music by traditional musician Hamish Napier.

I am also appearing at the Nairn Book & Arts Festival this Friday 10th September to share about the book. You can get tickets here.

On this night, eight years ago, I started writing my novel, Of Stone and Sky. It was the summer solstice here in the Highlands of Scotland and I was woken at 3am by the light and an idea that kept tugging on me. Finally, I got up, went down to the kitchen table and started writing on a blank sheet of paper. The first words were, “A story. A land. A people. This place of beauty and history, of loss and hope. A shepherd.” Top right of the page it says, “4am, 22 June 13 – The shortest night”.

For a long time, The Shortest Night was the working title of the book, initially because that’s when I started it, but also, as the story emerged, because the summer solstice became the point of emotional climax for one of the central characters. That event happens right at the end of the book at the summit of Angel’s Peak, a mountain in the Cairngorms whose Gaelic name is Sgòr an Lochain Uaine – the Peak of the Small Green Loch.

It’s a tough walk to get there and I’d never been, writing the chapter based on walk reports and photos. But in eary July 2019, feeling overwhelmed by life and in need of a mountain, I went up with my husband, Alistair, and our golden retriever, Sileas, (Gaelic for Julia.) By then, the novel-in-progress was on its third title – Colvin’s Walk – but on a much higher rejection count, which was a significant source of my stress. The account of that trip and how it changed me, can be read here. On that occasion, because of the dog and our uncertainty about the route, we didn’t take the steep scramble up the north ridge of Angel’s Peak that my character Sorley takes in the novel, opting for a safer traverse.

Now, two years later, Of Stone and Sky has found the right title and the right publisher in the wonderful team at Birlinn/Polygon Books and is rapidly finding happy readers. Which is the whole point. This past weekend, in order to celebrate, to give thanks, and to walk the path of Sorley as he searches for his brother Colvin on midsummer’s night, we went back up to Angel’s Peak. This time, we swapped the dog for our professional Mountain Guide friend, John Lyall, who led us up the ridge.

And before I went, I registered Of Stone and Sky on BookCrossing.com. Bookcrossing is a way of releasing books into the wild for others to find, read and pass on. I did the same thing with my first novel, A House Called Askival, planting a copy on the top of Askival, the highest mountain on the island of Rum, for which the house in a hill station in north India is named.

Wonderfully, it was found a few days later by a delighted book-lover who shared the news and later released it at the Ryvoan Bothy in the Cairngorms (little knowing it is my stomping ground). I’ve never heard about its journey from there, but perhaps it was fed into the fire on a particularly cold night… Or perhaps, hopefully, it fell into the hands of another book-lover and is still travelling.

And so, like offering the ‘angel’s share’ of a barrel of whisky, I left a copy of Of Stone and Sky at the top of Angel’s Peak. In order to fend off the notorious Cairngorms weather, I double bagged it, put it in a tin, double bagged it again and taped it up like a parcel bound for the moon. The best container I had for the job was a shortbread tin and it seemed a perfect choice for historical fiction set in the Highlands, with its tartan, glass of whisky and Dean’s Shortbread strapline, ‘History in the baking’. But there’s a wry irony too. While Of Stone and Sky certainly does serve up a hundred years or so of Highland history, it’s not melt-in-the-mouth. In fact, more than one reader has commented how the book is NOT the shortbread-tin version of Scotland. I do hope, therefore, that the finder of the tin – and, indeed, my readers – will not be disappointed.

As well as the book in a deceptive tin, we took a very special shepherd’s crook into the Cairngorms. The full story of our walk – and the crook – will be in an upcoming post. For now, I leave you with an extract from that chapter in the novel where Sorley makes the trip.

“Three years after my brother disappears, I make my slow way up the walk they took when I was just a light in my mother’s eye, up through the pass of the Lairig Ghru in the Cairngorm mountains and into the Garbh Choire. It is midsummer’s day and the smells of moss and peat rise around me in the warm air, cotton clouds drifting in the high blue. Stones shift under my feet and hands as I pick a route up the rocky slope to the Lochan Uaine and the waterfall where the MacPhersons’ key was found. Hip throbbing, sweating, I pull off my pack and ease down onto a rock, enjoying the cool air on my damp back and hair. Above me rise the twin summits of Cairn Toul and Angel’s Peak, together forming a curving wall of steep cliff and scree slope that shelters me from the full force of the wind. Stretched out between me and the foot of the cliffs, the lochan is a vivid blue-green, deeper than the sky. Its surface is lightly brushed with ripples, edges lapping on pebbles that all look grey at first, but gradually reveal their colours, from pearly white to peach and pink, mottled mauve and black.

…

I lie that night on a mossy ledge beside the lochan, the hood of my bivvy bag unzipped so I can stare at the sky. It never quite gets dark but glows a deeper, lovelier green by the minute, drawing me into drifts of light sleep and welcoming me back as I wake to the sound of a bird or a voice in my dream. Each time, I find the moon has travelled, a silver canoe rowing the deep. In the very early hours, with the sky softening to pink, I see a deer a few feet away. She is young and delicate, one hoof lifted, her eyes fixed on me. We watch each other, barely breathing. Then her ear twitches and she shoots away, so swift and quiet it seems she is spun from light.

It’s 3 a.m., but I get up, drink from the cold lochan and climb the curving north ridge beside it to the summit of Angel’s Peak. It is slow and painful, and I am light-headed from hunger and lack of sleep. By the time I get to the top, the sun has risen and washed the whole of the Cairngorms in gold.”

As well as a free one on top of Angel’s Peak, copies of Of Stone and Sky can be found here.

Here in the Cairngorms, Winter has put on quite the show. I know it might not be over. There is probably more snow and ice to come – especially on the mountain tops – but as Spring makes her entrance and tries to usher old Winter offstage, I wanted to catch him in the wings and say thanks. You were amazing, dahling. Unforgettable.

There are rumours that the temperatures dropped to -20 celsius one night. Certainly, it stayed cold for weeks and the lochs in the valley froze over, with people walking, skating, ski-ing and cycling across them. Swimmers hacked through the ice to take dips and I even joined them: once on New Year’s Day, once in February, and once on International Women’s Day last week, when the ice was melted and it sounded for all the world like the ducks were laughing at me.

So, here are some stills from Winter’s glorious run at the Cairngorms theatre. I hope you will enjoy looking at them as much as I enjoyed living them. And for the story of a magical paddle across Loch Insh, just days before it started freezing, have a look at Winter Canoe.

Looking to Braeriach from Sgor Gaoith, the Windy Peak

Winter berries

Ice formations in a mountain burn

A hill called An Suidhe

The island in Loch Insh

From fields and forest to the Cairngorms

Frosted boulders on a Cairngorms ridge

On Carn Ban Mor, looking across to Braeriach

Scimitars of ice

The Wolf of Badenoch’s castle on a frozen Loch an Eilein

Highlanders gather in defiant flouting of lockdown regulations

Looking across the Uath Lochans to the Cairngorms

A frozen puddle

On Geal Charn, Monadhliaths

A pattern of crystals on a seam of snow

On Loch Insh, Cairngorms behind

A watery Loch Insh

Woodland mushrooms

Cracked plates of ice

Laggan valley from Creag Dubh

Glaze ice on stalks of grass

Lantern Waste, Narnia

A winter slope

Frozen marshland

Melted droplets on Scots Pine

Across the Spey to the Cairngorms

Walking on Water – Loch an Eilein

Sunset

The coming of Spring also means the launch of my Cairngorms novel, Of Stone and Sky, which is incredibly exciting. (For me, anyway.) Keep May 6th free to join us for the launch (time to be confirmed.) It will be digital, which I know is tough on all of us already utterly Zoomed out, but it does mean more folks can attend AND, fear not, we have lots of fun things up our sleeves. In the meantime, follow the series of Signs in the novel on Twitter, Facebook or Instagram.

Till then, do share with me some of your magical Winter moments – or Summer ones, for those in the southern hemisphere! It’s a beautiful world.

It was one of those lost days between Christmas and New Year when we should have been travelling home from family in Yorkshire but had been forced, like most of the country, to stay home. The house was awash with decorations, dishes, dust, dog-hair, leftovers, chocolate wrappers, dribbled candles, pine needles, new books, old newspapers, drifts of ribbon, cards and all the other detritus of the washed-up festive season. With no-one allowed to visit and no plan for Hogmanay, comfortable mess was tipping into squalor. The weather forecast had prophesied an overcast day and I was girding my loins for an intrepid expedition to Raid the Cleaning Cupboard, Restore the Lost Hoover and Rescue the Rarely-spotted Toilet Duck from extinction.

By a stroke of exceptional good fortune and – I maintain – divine intervention, I was spared this fate. The sun came out. With it, a winter wonderland of snow, frost and sparkle began to woo me from beyond the grubby windows.

Who was I, dear reader, to ignore such a celestial summons? The scales of domestic duties fell from my eyes and with the evangelical fervour of the new convert, I immediately set out to save another. Marvellously, my friend and neighbour down the street, Shula, proved as easily redeemed as I, and within half an hour we had forsaken our former lives and were rooting around in her garage for the vestments of our new calling. Life vests, neoprene gloves, paddles. We were heading for a boat.

Canoeing is not something I’d ever contemplated in the middle of winter before. A previous four-day expedition down the Spey in early April had been so blighted by cold and rain that we’d turned heel and scurried home to warm fire, food and beds on the first night. (Whatever Damascus Road experiences I may succumb to, they rarely rob me of my creature comforts.) The only reason paddling seemed like a good idea this winter day was because it was brilliantly clear and windless and because we’d never gotten around to bringing our canoe home from the lochside at the end of summer. And because it was something I’d never contemplated before.

Even the walk to the loch was captivating, the trees bowed with snow like a worshipful multitude, the sun shafting through the branches and sparkling off every crystal. On the shore, two fishermen sat perfectly still by their rods under frosted birch trees. There was a soft crackling as the warming sun melted the ice in the branches and it fell on us in bright flakes. The loch was a mirror to the trees on the island opposite, the white hills, the sky.

We pushed out and drifted far down to the southern end. When I say ‘drifted’, I mean mainly me, gasping at the scenery and taking photos, while Shula steered and paddled. Another good reason for waylaying her is because she has canoe qualifications and is eminently sensible. Even under my influence.

In the shallows, fragile panels of ice hung in the rushes inches above the water, showing its height at freezing. Loch Insh is simply a swelling of the River Spey and like the rest of the river in this wide strath, is prone to flooding and dramatic shifts in level. In fact, the Gaelic name for our area is Badenoch, which means ‘the drowned lands’. South of the loch, the Spey snakes in wide loops across the Insh Marshes, an area once drained and tamed for arable farming, but now returning to nature. Rich in birdlife and flora, it is one of the most significant areas of wetland in Europe and managed by the RSPB.

At the far end of the loch, black cormorants dried their ragged feathers on a half-drowned log as goldeneyes beat across the water, their wings whistling. Our boat slipped quietly into the mouth of the river, past the alders and willows as far as a curving sandy beach where the swans nest, before we made the long, lazy (for me) return. The mute swans are always here, their radiance echoing the snowy hills and the old white church above the loch. They share these waters year round with the ducks and gulls, joined in summer by dozens of breeders, like the osprey, and in winter by northern guests, like whooper swans.

Somewhere in the middle of this splendour, Shula multiplied the miracles by pulling out a flask of Rooibos tea and a plastic tub of home-made gingerbread biscuits. I shall have to lead her astray more often. We floated in the centre of that hushed winter arena, the blue tent flung wide above us, white hills circling, the loch a stage set for a pageant in which we played only the tiniest part.

Dragging the boat back up the pebbly shore and crunching home across the snow, I could barely remember my past life as a domestic mortal. And though I would return to the old dispensation, still littered with the artefacts of a normal life, it would not matter anymore. For my home, like my head, would be brimming with visions of a greater world and ringing with its call.

(now the ears of my ears awake and

now the eyes of my eyes are opened)

e.e. cummings

To join Shula on a canoe expedition with the Alltnacriche outdoor centre (in the summer!) click here.

To read my Christmas Eve piece in the Guardian Country Diary click here.

To listen to my New Year’s Day short story on BBC Radio 4 click here.

To follow the trail of 12 Signs to the April launch of my novel, Of Stone and Sky, follow on Instagram, Facebook or Twitter.

To keep up to date with all of it, sign up here!

The regulars were arriving for their slap-up Christmas dinner. Some faces glowing, others uncertain and sad. Damp coats steaming on the hooks above the radiator. Winter-chapped hands fumbling with paper hats.

It was the monthly meal for the homeless provided by our church and I was one of the team. Every month we served a three-course meal, but tried to make it extra special at Christmas, with crackers, decorations, music and gifts. Most of the folk did have some sort of accomodation and we asked for no proof of need, but just welcomed all who wanted to be there. And it was moving to see who came and how homeless the heart can be.

That was back when our own home was a two-bedroom flat in Stirling with two pre-school boys filling the space and my writing desk wedged a couple of feet from my pillow. So when I got an email from Kirsty Williams, BBC Scotland radio drama producer, asking if I had any ideas for a story about food and memory, I didn’t have to ponder. She was curating a series called The Madeleine Effect inspired by Proust’s In Search of Lost Time in which eating a madeleine, the small French cake, transports him to the past.

Not long before, I had heard a story from a local family that had shocked me. And so, being the magpie writer that I am, I borrowed elements from those events and kneaded them into my experiences of the homeless meal, along with other images, stories and memories that appeared like seasoning on the shelf of my imagination – or indeed rose out of the loaf unbidden – until the tale Broken Bread was formed.

As the Christmas angels said, Be Not Afraid. No unsuspecting people were harmed in the writing of this story. Names, cultural backgrounds, events and identifiers are all changed. People sometimes think they recognise themselves or others in my writing, but they are usually not the people I had in mind. Perhaps we all recognise ourselves in stories. Perhaps we should.

Broken Bread was read beautifully on Radio 4 by the very fine Scottish actor Gary Lewis, who I know best for his role as the father in the film Billy Elliot. Alas, the recording is now buried in a BBC archive and not available to hear anymore, but I still have the text. I’m extending it to you now as a gift. In order to download it, you will have to sign up for my newsletter, but you can unsubscribe straight away and still keep the story. I won’t tell anyone.

Or you could stick around and enjoy the conversation. There is always news of the happenings from my desk and beyond, what I’ve been up to and where I’m headed (if only I knew) as well as special offers and opportunities for subscribers only. And if you respond, I will write back. So come and swap tales with me, break bread in spirit, share life. There is always room at the table.

With thanks to Ian Campbell for permission

Wherever you are, at the end of this strangest of years, may the season of light in darkness bring your heart home.

Broken Bread is here and listen out for another Radio 4 Story on New Year’s Day.

The ospreys have gone. I went away for a week and when I got back, the strath had slipped into autumn and the eyrie above Loch Insh was empty. On the same day, my two sons returned to university. Their courses will be online, but after five months of being back under parental wings they are ready to stretch their own again. They came back to our Highland home at the start of lockdown and two weeks later, the osprey arrived, flouting all restrictions in their 6,700 kilometre journey from west Africa.

The male came first and began to ready the nest, a large twiggy crater the size of a truck tyre. Balanced precariously at the top of a tree on a small island, it has commanding views of the Cairngorms to the south-east, the Monadhliaths to the north-west and the River Spey between. Their arrival always speaks to me of Mark, a wildlife guide friend who first told me their story on these shores five years ago; he was diagnosed the following April with a brain tumour and died in April two years later, leaving a wife and three sons. As he was lowered into the earth of Insh churchyard, the newly returned osprey soared above.

Most osprey pair for life, only coming together during the breeding season when they return to the same place. The female arrives a week or so after her mate and my diary note from April 16th says: ‘Both perched on the nest, looking at each other from time to time and touching beaks.’ As the female adds to the eyrie, the male woos her by delivering trout. One of the few birds of prey to live almost entirely on fish, osprey can see their underwater catch from 40 metres up and have reversible talons that help them grip. Working from home this year, I paid closer attention to my near neighbours. I saw the male perform his sky dance, crying out as he rose in sweeping circles above the nest with a long reed in his talons. The female sat on the spear tip of a dead tree nearby, motionless and haughty as Horus.

By the beginning of May, she had settled down in the nest, presumably won over and incubating eggs, and I watched and waited through the lengthening days and the greening of the strath. At last, in early June, tiny heads appeared above the twigs – one, two… three! A beautiful, bumper brood and the most an osprey is likely to hatch. I caught glimpses of the mother feeding them and the gradual rise of their small, fluttering bodies.

One evening, a large heron flew up the river towards the nest and the male osprey bore down on it with vicious shrieking and flapping of wings. To my astonishment, the heron did not beat a hasty retreat but kept circling, evading the ever-more strident attack. Finally after several minutes of this aerial dogfight, the heron – twice the size of its assailant – made its stately way off down the loch.

Summer swelled and the loch thickened with green rushes and the growing company of birds: curlews, oyster-catchers, martins, geese, ducks and swans, many trailing flotillas of young in their wake. Both my boys were summer babies and these long, light days remind me of that ecstatic, exhausted time. By mid-July the osprey chicks were stalking the rim of the eyrie, stretching their wings and lifting for moments into the air while the parents sat in nearby trees calling. To urge their young to fledge, osprey gradually reduce the fish they deliver, literally starving them off the nest. We have not resorted to such ploys but, like all parents, we know the push and pull of need and independence.

Who can know if they have witnessed the first flight of a bird? I cannot, but I thrilled to see them gradually take to the skies, their voices ringing in the amphitheatre of this hill-bordered loch. Who can hold onto life? It was at this time that our beloved friends, Mark’s family, moved away.

All five osprey were in the nest when I looked in late August, but within two weeks, they were gone. The mother goes first, travelling up to 400 kilometres a day till she is back in Senegal. The father follows and then the young, flying all the way down over the Sahara. They travel alone. No one has fathomed how they know the route or the destination or how, three years later, they know the way back. It is mystery and miracle. All I know is that in the great, thick hush of these five months, when my own dear ones came and left, the osprey’s journey has passed right through my heart.

This article first appeared on Elsewhere A Journal of Place