Living by the Spey, most of my walks into the Cairngorms are from the north-western side, such as the one to Angel’s Peak last year. I’ve always wanted to venture in from the Deeside on the south-east, walking up to Loch Etchachan and Ben MacDuie, so on a recent weekend we drove round the top of the mountains to begin a three-day camping trek from the Linn of Dee near Bramar. We were blessed with endless sunshine, but the unusually still air meant we were also cursed by Scotland’s smallest and most infuriating fiends: the midges! Apart from their invasions morning and evening, it was a trip of radiant light and colour, of long days and far views, of rushing water, birdsong and quiet. I’ll let the photos tell the story.

We got to Braemar by 5.30 that evening, extremely thankful for hot showers, a pub meal and a huge soft bed. But even more thankful for three days walking, swimming, sleeping, looking and listening in the Cairngorms.

“However much I walk on them, these hills hold astonishment for me.”

Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain

What happens when we pay close attention to nature? A Sense of Place, about my residency with the Cairngorms National Park, first appeared in the 2020 Summer issue of The Author.

‘Do you see them? There’s a ruby – and over there, a sapphire!’ The senior gentleman points his walking stick into the long, frosted grass where melting droplets are firing with all the colours of the prism. The more we look, the more jewels we see, winking brilliantly in the November sunlight. Later in the pub, they read me their poems.

In stillness by the river, a woman gathers sounds and memories that take her back to a childhood walk and a kind lady’s biscuits. She writes the story for the first time and glows with the telling.

A schoolgirl sits so quietly in the woods that a ladybird roams over her finger and into the words on her page.

These are just some of the encounters that have stayed with me from Shared Stories: A Year in the Cairngorms – my project as the first-ever Writer in Residence for the Cairngorms National Park, which ran throughout 2019. The aim was to encourage participants to express in words how people and nature thrive together.

The relationship between humans and the natural landscape is a key priority for the Cairngorms National Park, which is the biggest national park in the UK and a unique, fragile environment. Half its land has international significance for nature, and it is home to a quarter of the country’s threatened species, including the red squirrel and the elusive capercaillie. At its heart are the Cairngorm mountains, a granite massif of connected summits. They were once higher than the Himalayas, but worn down by glaciers, wind and weather over millions of years, they are now rounded humps that can be climbed in a day and appear deceptively easy. The reality is much harsher. Rising above the mellow straths, the plateau is a small slice of the Arctic, with a climate as dramatic and dangerous as the rock faces that woo climbers from around the world.

Successive generations of those mountaineers have sought to capture their experiences in writing, often with as much determination and passion as their attempts to conquer the rock. Notable Cairngorm writers include W.H. Murray, whose 1947 masterpiece Mountaineering in Scotland was written on toilet paper while a prisoner of war. When the manuscript was destroyed by the Gestapo, he doggedly began it again. The book is testament not only to his love of the mountains, but also to their power – and the power of writing – to elevate him above wartime despair. Describing the summit of Lochnagar, he wrote: ‘Over all hung the breathless hush of evening. One heard it circle the world like a lapping tide, the wave-beat of the sea of beauty… We began to understand, a little less darkly, what it may mean to inherit the earth.’

Another remarkable Cairngorm author and Second World War vet was Sydney Scroggie, who trod on a landmine in the final fortnight of the war and lost half a leg and his eyesight. A hillwalker from boyhood, he said, ‘I can do without my eyes, but I can’t do without my mountains.’ He went on to make 600 ascents with walk companions and wrote the book The Cairngorms Scene and Unseen. Often walking shirtless, his writing bears witness to the intensity of the sensual experience but also the importance to him of the ‘inner experience, something psychological, something poetic.’

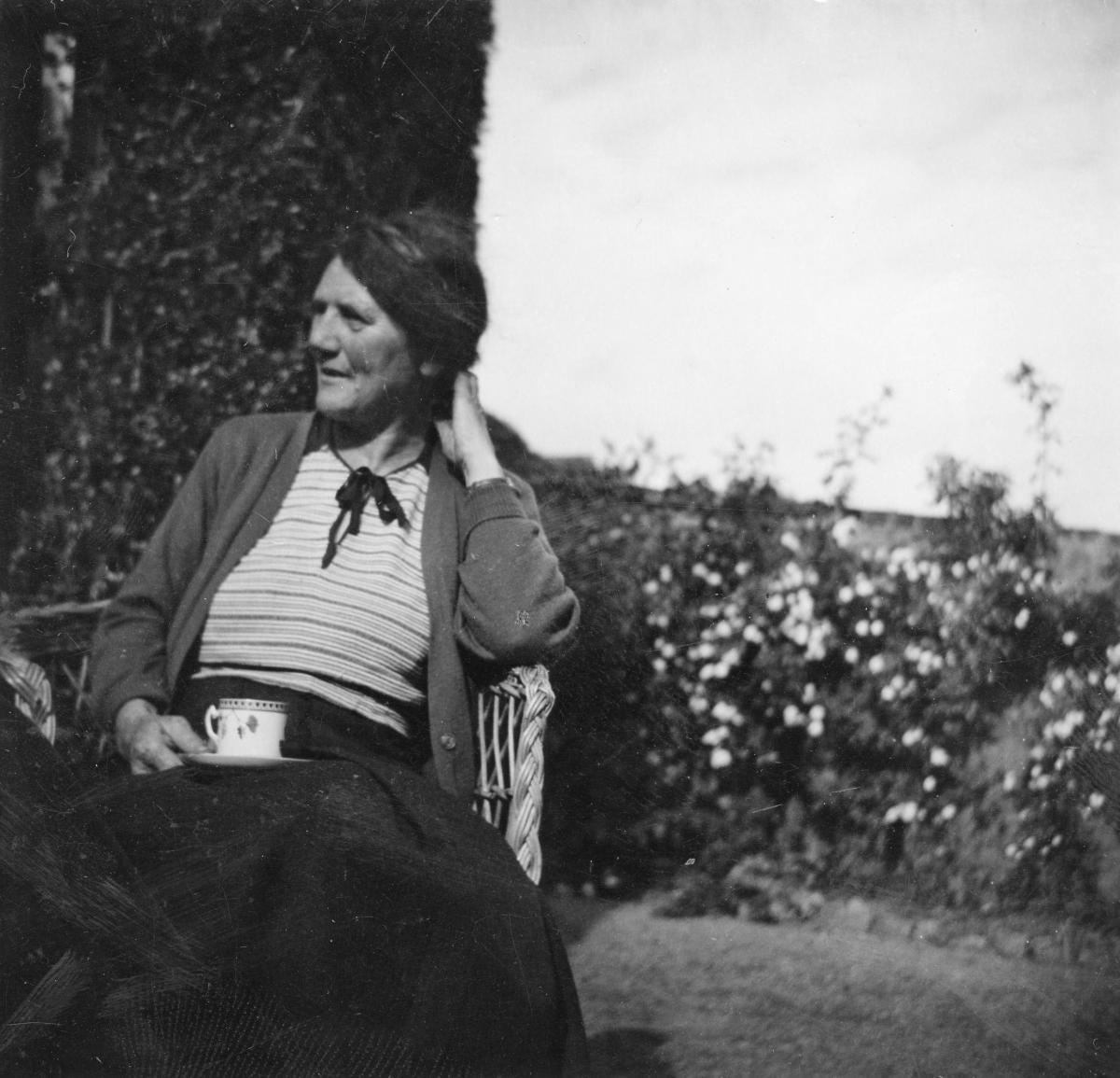

While these men were away at war remembering the Cairngorms, a woman was walking them and writing a book that was only published 30 years later and not truly recognised for another 30 after that. Nan Shepherd’s slim volume, The Living Mountain, is unique in adventure literature and far ahead of its time. Just as her goal as a walker was not to summit the mountain, her goal as a writer was not to document the route or its challenges and triumphs. ‘It’s to know its essential nature that I am seeking here,’ she wrote. Her life-time of deep exploration took her across all the Cairngorms’ terrains and weathers at all paces from running to falling asleep. Throughout, she committed to this ‘traffic of love’ with every fibre of her being.

Inspired by all the Cairngorm writers, but particularly in Shepherd’s spirit, I approached the Shared Stories residency as a pilgrimage of discovery. Although one workshop was with the hardy outdoor instructors of Glenmore Lodge, most of our participants were not mountaineers or trying to pit themselves against the Cairngorms. Many were children and several were over 80, so Shepherd’s approach made sense. Never casting herself as a sportswoman, she was an English lecturer at an Aberdeen teacher’s college and, according to her biographer, Charlotte Peacock, always walked in skirts.

That is, of course, until she walked in nothing at all, which was what she did to enter the cold lochs high in the clefts and corries of the range. Because to Shepherd, the aim was full immersion, a whole-body experience of the mountains that called on all her senses, and both seized and superseded her mind. ‘Here then may be lived a life of the senses so pure, so untouched by any mode of apprehension but their own, that the body may be said to think.’

Senses, therefore, were a key starting point for nearly all the Shared Stories workshops. Wherever possible, I took groups outside and we spent time falling still in the natural world, working our way slowly through each sense, scribbling down the words that came. It never ceased to astonish us how much was revealed when we paid that kind of close attention, even in very familiar places. One group who walked regularly beside the River Gynack, stopped with me on a small wooden bridge and with eyes closed, simply listened. We realised that the stream did not have one sound, but many, like an invisible orchestra with a percussion section, bass notes and an ever-shifting melody. Afterwards, a man from the group sent me a poem and this note: ‘Thank you for opening our eyes and ears on the walks.’

Smell is a sense often ignored until it is assailed, so we needed to get in close to notice the subtleties. Clumps of bark covered in moss yielded a surprising medicinal fragrance quite different to the smoky darkness of peat. And though our generalised image of granite might summon shades of grey, looking closely at Cairngorm rock reveals that it is actually pink inside. Even on the grey surface, the patterns of lichen are full of colours: yellows, lime greens and ochres. And though we may be most protective of the sense of taste, sensibly, we opened our mouths to nature, too, in the taste of wild berries and the tingle of snowflakes on the tongue.

Touch, I learned, is something to be explored with far more than our fingers, as Shepherd, Scroggie and Murray testified, all of whom plunged into mountain lochs. In Scotland, especially, where we spend so much time bundled into layers of clothes, it is startling to peel off and allow the water and weather to reach us. But when we do, the experience is arresting, the focus total. And often, the words that arise are equally rewarding.

The process, therefore, of paying attention with our whole bodies proved vital not only to experiencing the world with more clarity, but also to discovering fresh ways of writing about it. Once we move beyond the clichés – the sky is blue, the grass is green – and seek to capture the truth of what is there, we are compelled to find new words. In a workshop for adults with learning difficulties, we stood under a forest canopy and brainstormed all the different words for green in the leaves above. Emerald, jade, turquoise, lemon, sage, olive. Through this tuning of the senses and intensifying of focus, we begin to recognise the dimensions and complexity of the world around us; the wonders that go un-noticed.

The project was undoubtedly successful for the participants and the Park, but what about me? Writing teachers often share that the energy and time of helping others create can drain your own resources and I certainly felt that way at times. I loved the project, but sometimes while participants were dashing off nature writing and saying how joyous it felt, my own well was dry. Over the year, however, deep things happened. I learned habits of stillness and observation; I captured notes, scribbles and fragments; I read the work of other great writers. And I dedicated time to poetry. My usual ground is fiction and drama, and though I’ve always written poems, in off-the-cuff scraps, I had rarely before invested the slow, patient work of crafting. It taught me how difficult it is to write the kind of poetry I really admire, but how much I wanted to. And perhaps that was the most important opportunity for me from the project: to have a year as Learner in Residence.

It’s the Cairngorms Nature at Home Big 10 Days! This WAS going to be the Cairngorms Nature Big Weekend and I WAS going to be over with the rangers in The Cabrach in Morayshire leading a family story-making session. Hopefully, all of that can still happen next year, but in the meantime the folks at Cairngorms Nature have organised a fantastic programme of virtual events from 15th to 24th May. That means people all around the world can enjoy this exceptional place while staying safely at home.

To mark the event, I’m sharing a nature poem each day on Instagram and Twitter. The ten together make up a series called The High Tongue, printed below, which were my contribution to our Shared Stories anthology last year. Exploring the names of ten of the Cairngorm mountains, each title begins with the anglicised version, followed by the Gaelic spelling (if different) and then the translation, which is explored in the rest of the poem. They are all Cairngorms Lyrics. This is a new poetic form I invented last year as Writer in Residence for the Park and you can read all about it here. (For pronunciation of the Gaelic names, look out for a recording I’ll post soon of me reading them all.)

Ben MacDuie – Beinn MacDuibh The Mountain of the Son of Duff High King of Thunder Old Grey Man Chief of the Range Head of the Clan Cairn Gorm – An Càrn Gorm The Blue Mountain Rainbow height: blaeberry bog brown red deer snow white blackbird dog violet moss green bright

Carn Ealer - Carn an Fhidhleir Mountain of the Fiddler She plays the rock with the bow of the wind for the stars to dance Cairn Toul – Càrn an t-Sabhail The Barn Shaped Mountain Storehouse of stone Boulders shouldering like beasts in this dark byre Hail drumming the watershed

Ben Vuirich – Beinn a’ Bhùirich Mountain of the Roaring Once the haunt of wolves howling at night now just their ghosts in failing light Coire an t-Sneachda – Coirie an t-Sneachdaidh Corrie of the Snow Bowl of white light black rock wind run ice hold hollow of the mountain’s hand

Beinn a’ Bhuird The Mountain of the Table Giants gather in clouds of black for a bite and a blether, bit of craic. Ben A’an – Beinn Athfhinn Mountain of the River A’an in a cleft of silence hidden loch secret river name breathed out like a sigh

Braeriach – Am Bràigh Riabhach

The Brindled Upland

freckled speckled wind rippled

shape shifting fallen sky

dark light shadow bright

land up high

Am Monadh Ruadh

The Red Mountains

Range of russet hills

forged in fire at first sunrise

old rust rock

glowing still

Do you love maps? I find them fascinating, so when I was invited by Walk Highlands to write an article about what to do when we can’t walk very far, Map Gazing immediately sprung to mind. It’s what I did for a long time before making my pilgrimage to Angel’s Peak and what I did for a long time afterwards, to savour the journey. A map, I’ve discovered, is not just an image of the land, it is a story about it.

Read the Map Gazing article (with fantastic photos from the Walk Highlands editors) here:

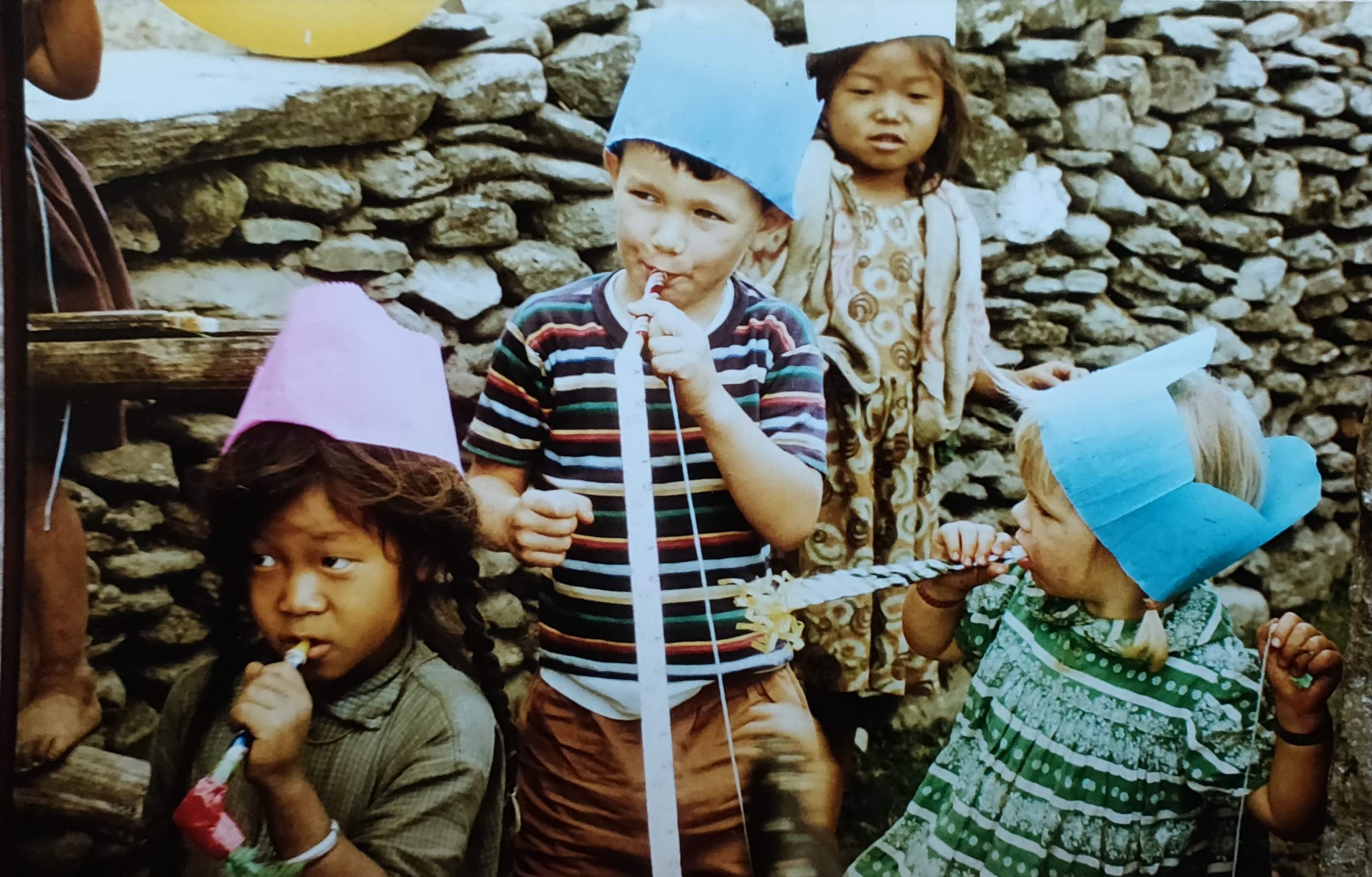

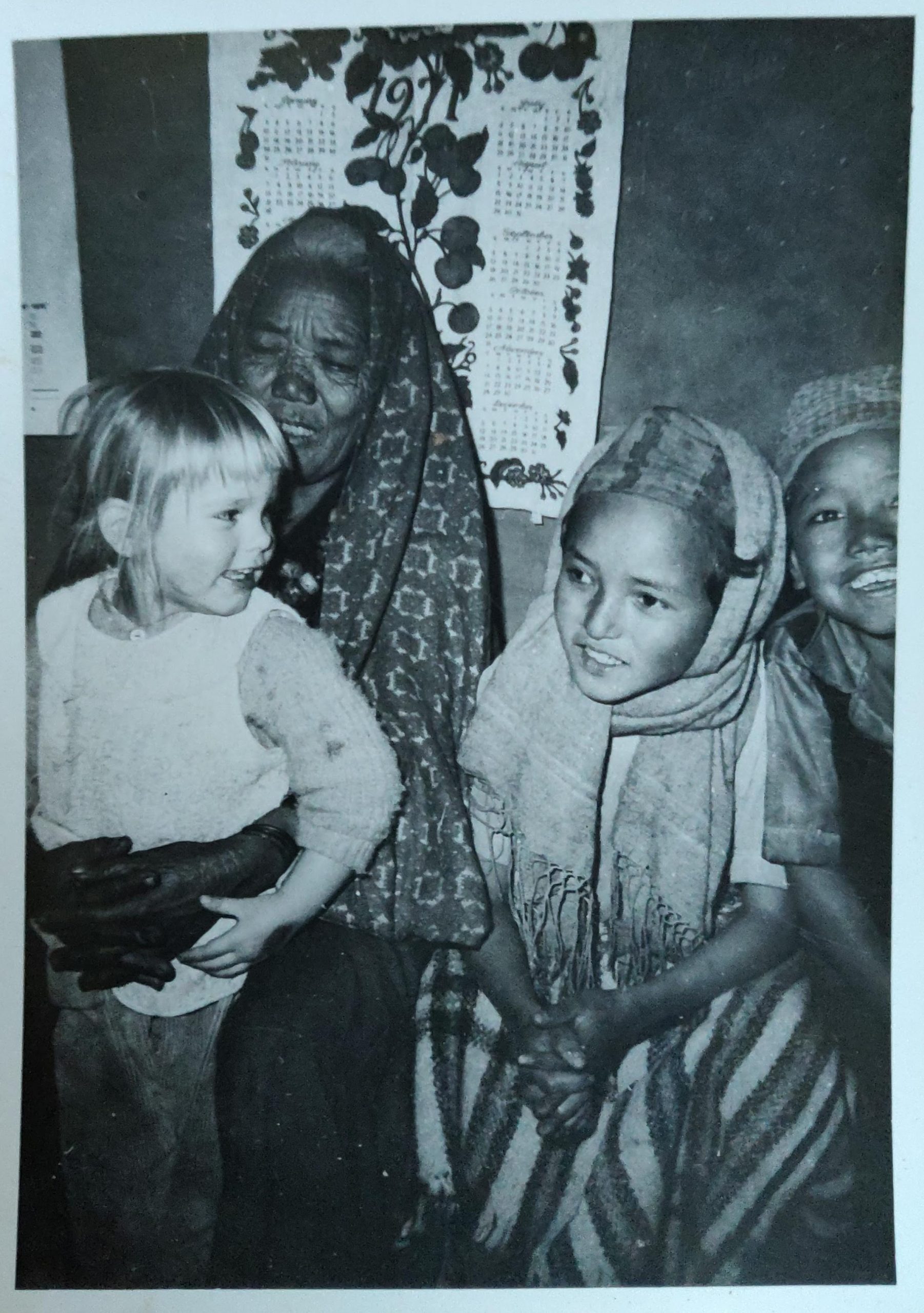

My head is still in the Himalayas. Two weeks ago, I shared about my childhood in Ghachok, a village in the mountains of Nepal which is home to the Gurung people. We left it in 1976, and over the years, have made several trips back. This is the story of those returns.

The first one was in 1984 with my brother’s friends. Not much had changed then except that Mark and I were now tall enough to bang our heads on the door lintel, which felt like the end of childhood.

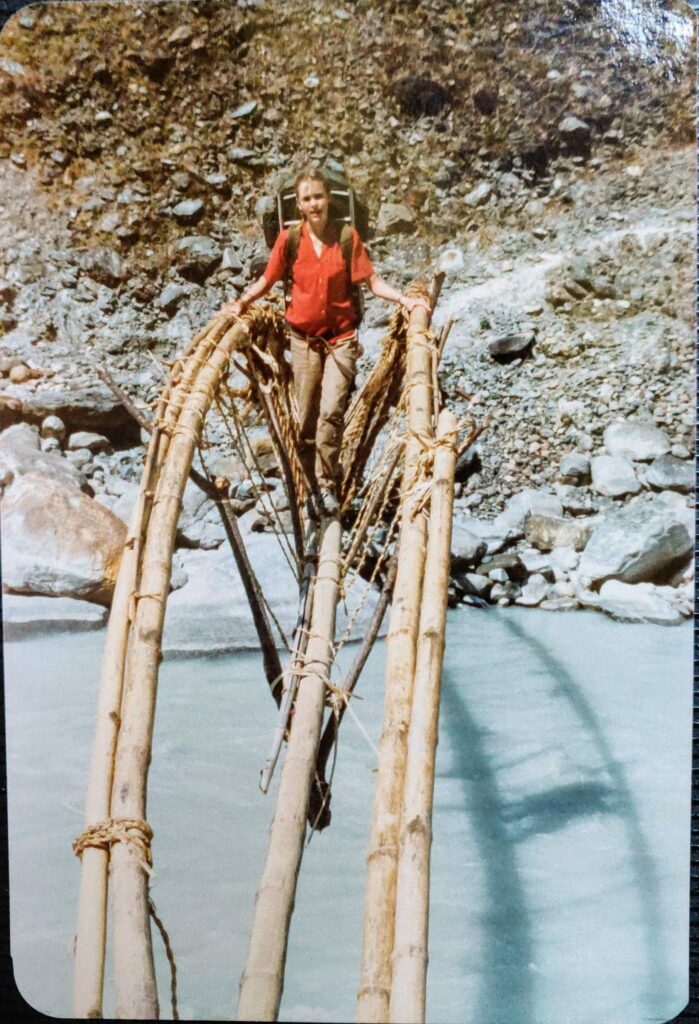

1984 on a familiar bridge

We noted on each of our visits how more of our village friends and neighbours were moving away, often to the town of Pokhara down in the valley, but equally often to places overseas. Many young men were serving the Gurkhas in far flung postings and many of the young women were married to them. On one return to Australia in 1987, we met our landlord’s daughter with her new husband in Singapore. The girl who used to tear round the village in bare feet and wild hair that she wouldn’t let anyone brush, had been transformed into a vision of beauty and grace. That entire family has now left the village.

In 1998, we were all working back in Nepal and with our parents, Mark and I took our growing families to see Ghachok: his wife and two wee kids, my husband and our baby, though he was just a tummy bean at the time. Our old house was vacant, so we slept in the musty room upstairs and peered out the back window at Machapuchare. The main difference by then was the establishment of the Annapurna Conservation Area Project and the replacement of goats – whose grazing habits inhibit forest re-growth – with ducks. They were great for curry but not so good for cuddles.

We went again in 2004 to celebrate my parents’ 40th wedding anniversary, with a few more children in tow, though my doctor husband and younger son missed out, as the latter came down with pneumonia. A pony helped the kids up the mountain and my Dad, with dodgy knees, back down. We went with a trekking company who erected tents for us at the edge of the village and it felt dislocated. Electricity poles and wires were marching up the plateau, but even more people had gone.

So when I asked to go again this year, as part of my parents’ farewell from Nepal, they were ambivalent. For our sake they would go, but didn’t expect many meaningful connections. We clocked the first major difference before leaving Pokhara: there is now a road and a regular bus that took us all the way there in 90 minutes, heaving and blasting its horn up the un-metalled track, a few kids piled around the driver for good measure.

The second innovation was the well-appointed Machapuchare Village Inn, where a friend had booked us for the two nights. It had spotless rooms with attached western bathrooms (no Time magazines), solar heated water and mobile reception better than the Highlands of Scotland. We walked above the village to find the springs where we used to picnic, but they were lost under the new forest and the dirt cutting for an extension to the road. There was rubbish underfoot, but overhead, scarlet and golden orioles rippled through the branches.

Some of the terraced fields looked abandoned, while others had been cleared by machine. There was no sign of the traditional ploughman with his yoked cattle, though, interestingly, the goats were back. Perhaps they are allowed now that enough forest has taken hold. Whatever the reason, they proved as adorable and obliging as ever, one even kissing me on the lips.

As we explored the village, to our surprise and delight, more and more of the old guard appeared and welcomed us with excitement: Abhwee! they cried. There was also cheerful critique in the case of my brother. Nepalis dye their hair well into old age and the men don’t grow beards, so Mark’s white designer stubble threw them. “Oh you’ve grown old!” they exclaimed. Or, “You used to look good!” He took it on the chin, so to speak.

As the oldest child, he had been named Surya (pronounced Soordzay) by the community, which means ‘sun’. The rest of the family are simply named in relation to the first-born (male or female): Surya-ma-aaba (father), Surya-ma-aama (mother), Surya-ma-nani (oldest girl). In a culture with close ties across extended families, there are distinct kinship terms covering most relationships: father’s eldest brother’s wife; cousin-sister on the mother’s side; youngest son; even younger youngest son (when a surprise turns up). Although everyone gets an official legal name, it is rarely used in childhood, and means there are multiple ‘nanis’ and ‘tagus’ scampering around the village; it also reflects the importance of the place within the family over the identity of the individual.

Mark was 7 months old when my parents arrived in the village and were given a vacant hovel to rent. Abandoned because it was allegedly haunted, their capacity to survive its maleficence perhaps changed its fortunes, as it has been in use ever since. As a baby, Mark spent many happy hours on a potty out the front waving to passers-by, so we took a commemorative photo on the same spot, though without the full re-enactment.

We returned to a second house where we had stayed (too young for my memory) finding the elderly owners now crippled by stroke. Sitting in their dark kitchen/living/bedroom, with him half-paralysed and her hobbling, we talked as their daughter-in-law made tea over a fire-pit in the earthen floor, a method unchanged in fifty years. Then she went outside and took a video call on her smart phone.

Back at the house where we had spent most of our time, we climbed the wooden log ladder to the verandah that had been school and dispensary. It was covered in corn cobs and the door to our living space was locked. Peering through, I saw the light from the northern window fall into a dusty cavern of corn husks and old bamboo mats. The ceiling was gone and the wooden beams gave way to slated darkness. It was hard to imagine the bright home that had been filled every night with people and the sounds of Gurung chatter, songs and even dancing.

But as we walked the old trails, more and more of those people remembered and found us again. One was Bara Hakim, a man with speech and learning disabilities whose nickname meant ‘Big Boss’ because he very ably commanded all around him. Then there was Goma-ma-aama whose son had been our playmate, and the widow of Purna, the porter who had delivered our mail and supplies. Another was Bobar Singh, the son of our neighbours up the path who had been desperately poor. It was reassuring to see he was dignified and well educated, though, like many, he has no work.

He insisted on guiding us around to Lasti Shon, a waterfall that had been a favourite picnic spot. Although the water is snow melt and icy cold, I have swum there on every visit and this occasion was no different.

Returning via the plateau rim, hundreds of feet above the Seti river gorge, we were stopped in our tracks by the sight of eagles riding the thermals. They took off from the cliffs below and passed us, their vast wingspans just feet away, before rising above, a dozen or more wheeling in the sun.

Another old acquaintance, Baru Kaji, got wind of our visit and insisted we eat at his home on our last night. Like many places in the village, his is now a Home Stay with support from Australian Aid and Australian Caritas. Though most village houses are still traditional with earthen floors and cattle sheds at the side, they now have external brick toilets and a courtyard tap. Many also have satellite dishes. Made entirely of organic produce from Baru Kaji’s own fields, our meal of rice, daal and curries was plentiful and delicious. One thing that hasn’t changed in Ghachok, however, is the wife preparing the food, serving everyone and then eating alone at the end. The position of women in Nepal has improved dramatically in the past fifty years, but they still have multiple challenges (of greater significance than dinner time etiquette.)

Our mornings in the village began with clear skies and the sunrise lighting Machaphuchare behind us. The quiet was touched only by the old familiar sounds of cocks crowing and people’s voices, carried easily on the windless air. And then the bus would arrive, rumbling and blasting its way up the road, under the concrete archway and past the multi-storey, multi-coloured Buddhist gompa. (There were none here even 15 years ago.) But that breach of the peace was nothing against our final night, when Nepali pop music was broadcast across the valley till 5am in celebration of a local wedding. In one bouncy song, a young man tries to woo his girl but discovers the price of love these days includes an iphone and a flight to America. (She’s certainly not eating last!)

One thing remained. On the final morning, standing in the sunshine with Machapuchare behind, I got my family to close their eyes and figure out the object I placed into their hands. It didn’t take too much fumbling and false guesses before they realised it was the old knitted dolls quilt. You can watch the moment here. There was something both gentle and powerful in the coming together of those hands that had made the quilt all those years ago; a family weaving back together in stitch and story.

They say you can’t go home, and we were all aware of the perils of nostalgia and the reality of change. But that journey was far more than a return to the past; it was an affirmation of a family’s life together. It was a difficult life at times and we are no dream family, but it was a life fired by a purpose greater than itself. We were ordinary people in an extraordinary place and I am forever thankful. To be there again together, for the last time, was gift.

I’d always heard about the forgotten glen round the back of Newtonmore, in the south-west corner of the Cairngorms National Park. There are ruins there and old, old stories. Someone said you could see eagles, and one of the Wildcat Trails goes that way. A long time ago, everyone went that way.

The locals pronounce it ‘Banachar’ but on the map it’s spelled Glen Banchor and arcs round the back of Creag Dhubh – Black Rock – the hump-backed hill that rises between the villages of Newtonmore and Laggan. Standing at the summit one freezing December, we looked down into the Glen, a span of silence with not a breath stirring the snow.

“Down there,” I said to my husband. “That’s where all the people lived.”

The following February we take mountain bikes into the Glen on a cold, breezy day. The sky is brooding and the Monadhliath mountains to the north form a dark wall. But where the sun breaks through, the fields glow and the raindrops in the bare trees turn to diamonds. Below us, the Calder makes the deep curve for which the glen is named: in Gaelic, a beannachar is a horn-shaped bend in the river. In the early days of Celtic Christianity, there was a monastic cell here dedicated to St Bridget of Kildare, and though nothing remains of the cell, the church in the village is called St Brides.

We cross Allt a’ Chaorainn burn at Shepherd’s Bridge and then Allt Fionndrigh, where we find the first of the abandoned dwellings. An old wooden barn and two stone houses, they were vacated recently enough to still look wounded and waiting. Like so many glens in the Highlands, this is a landscape of loss. At its peak in the late 18th century, between 300 and 400 people lived here in 14 ‘townships’, the cluster of dwellings that shared grazing. There was no bridge over the Spey then – the bigger, faster river in the wide strath on the other side of Creag Dhubh – so Glen Banchor was the major highway north for cattle, goods and travellers.

It’s almost impossible to imagine that now, as the trail rapidly dwindles into muddy grass, leaving us to churn through bog. Much of the time we have to get off and push, or even carry, the bikes. Occasionally a path resurfaces, but then vanishes again or forks into sheep tracks that head in unpromising directions. We keep scouring the map and the landscape for the route we’ve missed, but conclude it has gradually disappeared, like the people.

This is the ghost story that haunts much of Scotland, where glens that were once populated – even in remote places – are now empty. There were usually several intersecting reasons for the departures: poverty, hardship and poor harvests; emigration to the cities and new colonies; changes in agriculture. But the most significant, and the most shameful, was the Clearances, where landowners removed subsistence farming peasants to make way for large flocks of sheep. A history well-known in Scotland, but very little beyond, it reached its peak in the early 19th century, and then gave way to the Victorian era and the rise of the Highland sporting estate when sheep were side-lined in favour of deer and game birds. But the people never came back.

If you know what to look for, you can see the ruins of their dwellings across the glen, most little more than stone foundations, others with bits of wall, or even a roof. High in the mountains, there are circles of overgrown rocks, the remains of the shieling huts where the women and children lived every summer, grazing their cattle and making cheese. And under the flooded ground and the blowing grasses you might detect the outlines of the old corn-lands and the ‘run rigs’, the raised crop beds that lie in dark ridges like the ribs of a buried giant.

It’s not just human life that is missing; north of the Calder there is barely a tree. This kind of barren sweep is so common in Scotland that many people see it as natural. Even beautiful. True, in certain lights there is a harsh beauty about these open reaches and the contours of heath and mountain. But it’s certainly not wilderness. Every inch of this landscape has been shaped by people for thousands of years and the reality is that most of it is damaged, with only a fraction of the plant and animal life it once had. It creates an environment that continues to degrade – the banks of the Calder are painfully eroded – and offers little livelihood for human or beast.

This impoverished state developed over time, influenced by climate change, timber extraction, agricultural shifts and the extinction of Scotland’s major predators – lynx, wolf and bear. But the major driver in the past two hundred years has been over-grazing by sheep and deer and the routine burning of heather to support grouse. Sheep numbers have dropped dramatically (as they are barely profitable, even with subsidies) but deer and grouse are maintained at artificially high numbers for field sports across large swathes of Scotland. These are hotly contested issues in a country struggling with multiple land challenges, not least the most unequal ownership pattern in Europe.

There’s no bridge or stepping stones over Allt a Bhallach, so we carry our bikes, ankle deep in freezing water, to a bothy on the far side. Desolate, its slate roof is giving way, its door and windows black; the sole room is full of sheep droppings and the back wall gapes onto the dark hills, half hidden in cloud.

We have muffins and a flask of coffee to warm us, then push on through the watery world. Within the great quiet there is the sustained rushing of the Calder and its tributaries, and the occasional gurgling of a startled grouse. Though only a few ragged patches of snow cling to the hills, the mountain hare bounding away over the moor is still pure white in its winter livery. I feel a shot of joy. Despite rare human traffic, wildlife here is scant. We don’t see an eagle and I doubt anyone would see a wildcat.

The clouds shift, one moment casting the whole glen in forbidding greys, then pouring sunlight through a gap and turning everything to gold. It reflects my feelings about this place: sad, yet also thankful for its solitude. Barely a crow-flying couple of miles from the A9, Scotland’s main arterial north, this is a valley of wind and wide spaces that opens the head.

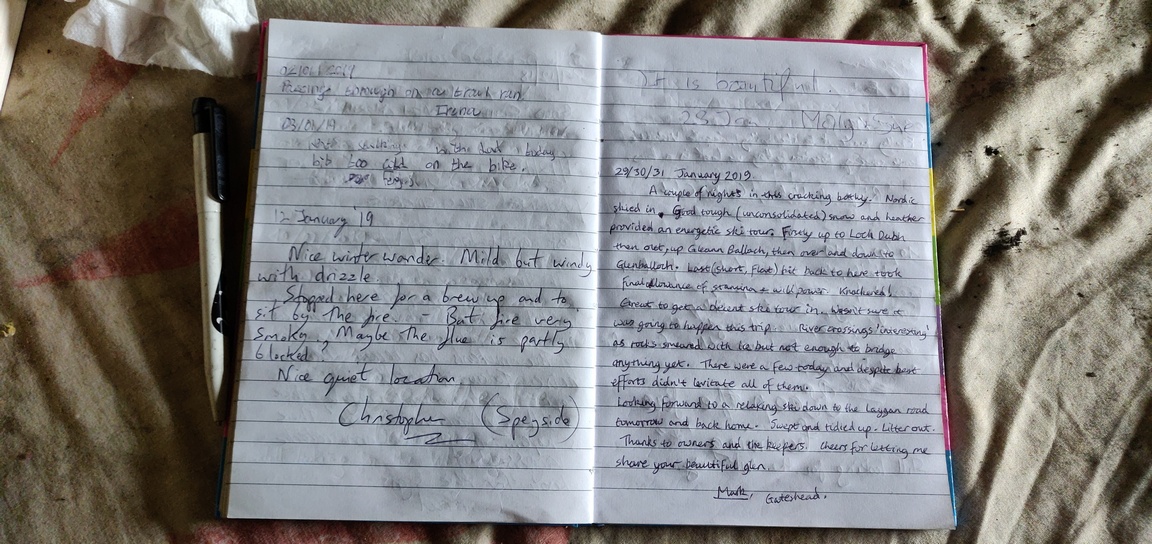

We ford another two burns, the last one churning up to our shins, and by the time I heave my bike up the bank, my feet are stumps of ice. We are now at Dalnashallag bothy, a stone hut with rusting corrugated roof used as resting place for wanderers. The main room smells ashy and damp, the fireplace wall smeared with soot, the couches sagging; an incongruous strip of floral wallpaper runs faded and peeling round the window bay. But spare as it is, the bothy book gives testament to its welcome shelter.

“Cycled from Balgowan with Andy and Islay the collie. Lovely evening for it. Just in time for tea.” Louise and Andy from Lancaster.

“It is beautiful,” write Molly & Sue.

“Talifa from Samoa island and Kallo from the Netherlands. Just passing by this warm house after a good walk in the hard lands.”

Yes, Glen Banchor is beautiful, but these are hard lands, and just as I hope its story is never lost under the grass, so too do I hope its story is not ended, but can be written in a new chapter, teeming with life.

This article first appeared on Elsewhere: A Journal of Place

From the comfort of my sofa in a warm living room, I have just booked myself onto my first ever mountain winter skills course. It is the middle of January in Scotland and having just returned from several weeks of the Australian summer, I feel plunged into darkness. Jet lag casts me onto the endless shores of the night where I lie tired but sleepless, listening to the silence that looms strange and total around the house. My parents’ old weatherboard house in Melbourne is a being of breath and bones, sighing with the see-sawing temperatures, bumping with the passage of creatures inside and out, caressed by trees. The Australian birds are raucous and the road busy.

Here in our village in the Highlands in mid-winter, even morning arrives without sound or light. I keep checking the clock to tell whether it is still some ungodly hour or time for breakfast. By day, rain washes across the landscape, clouds mass and shift with the wind and this morning we woke to a fall of wet snow that by afternoon had dribbled into the mud. None of this inspires me to go mountaineering. Nor does the whole-body misery of bubbling cold, sinusitis and jet lag.

But I want to write a book about the Cairngorms in all their moods, so I need to get up there and broaden my experience. Although I’ve walked in snowy hills many times, it’s always been with more experienced walkers and not long treks or demanding conditions. Late last year, therefore, I became a member of Mountaineering Scotland and this year I need to go on one of their highly recommended Winter Skills courses. The problem is they’re all booked up.

Until a few days ago when an email arrived offering a space on a one-day course this Wednesday – three days’ time. My heart sinks. I should be excited by the opportunity, but I’m feeling rotten and the last thing I want to do is spend nine hours in freezing conditions throwing myself down snow slopes for ice axe practice. Besides, the combination of the festive season, heat in Australia and this virus means I’m not exactly at peak fitness. But I know this might be my last chance this winter, so I gird my loins and book, noting that – at this late stage – no refund will be possible on cancellation.

Reading the kit list, I then note I will need to make a trip into town the following day for proper winter boots, crampons, ice axe and seriously waterproof trousers. (My current ones are budget brand, have lost their seam tapes and are about as effective as a pair of plastic bags.) But ouch. The cost of all that gear may wipe out any author earnings for the book. Wondering how many warm layers to wear, I check the Scottish mountain weather forecast for the day of the course. Here are extracted highlights:

HOW WINDY?

Southwesterly 60-80mph; risk gusts towards 100mph on high tops.

EFFECT OF WIND ON YOU?

Atrocious conditions across the hills with any mobility tortuous; severe wind chill.

That sentence goes through me like a 100mph gust of freezing wind. No, no, no. This is not me. I’m a happy-go-lucky hillwalker, not a polar explorer pitting myself against the elements and prepared to get frostbite, hypothermia and snot crystals hanging from my nose. And it’s not that sort of book I’m writing, anyway: the adventure epic of agony and conquest, the heroic survival memoir pushing the limits of bravery and belief. Who needs a mountaineering disaster? I’m touching the void of my existential crisis right here on the couch.

I go to bed feeling not just unwell, but frankly terrified. Little wonder I barely sleep.

The following afternoon, we head into Aviemore. If there’s one thing this town excels at, it’s outdoor shops, and we do the rounds. My husband Alistair is an experienced hill-walker in all weathers and advises me on winter walking boots, the pros and cons of stiffer soles or a more flexible fit, the lacing techniques. I’m struggling to get my head past the price tag. And that weather forecast. It’s only 2 o’clock in the afternoon, but already the darkness is gathering in the wind-blown skirts of rain. A friend who works in one of the shop learns I’m doing the course this Wednesday and winces. My stomach twists.

The news calls it Storm Brendan. It’s always bad news when the weather has a name.

I’m shown a series of ice axes and Alistair and the staff cheerfully demonstrate the necessary grip to arrest your fall and discuss the pros and cons of leashes. Pro: you don’t lose it. Con: if you fall without getting a grip, the thing is bouncing around and can hit you in the head. The good news is that Mountaineering Scotland will issue us with helmets. The bad news is that my head is already throbbing.

I haul waterproof trousers over my jeans and hubby points out best features for keeping rain, snow and wind out. I silently note that, even in the sale, these are more expensive than any dress I’ve ever bought. We end up in Tiso’s where I plea for time out in the cafe. With tears dripping into my hot chocolate I confess my anxieties. “Do I need to do this? Do I need to buy all this stuff?” It all just seems so scary and expensive.

Alistair is gentle. “No, you don’t have to do the Winter Skills course on Wednesday.” I almost howl with relief. “But yes, if you want to explore the Scottish hills in winter, you need to be safe. For that, you need proper equipment and better skills. You do need this stuff and it will last for years. And there are other opportunities to get the training, so don’t worry.”

Come Wednesday morning I can’t resist another sneaky peak at the mountain weather forecast. It still has those devastating predictions of 100mph gusts and ‘atrocious conditions’ but now includes these lovely lines:

HEADLINE FOR CAIRNGORMS NP AND MONADHLIATH

Stormy winds. Snow & whiteout, focused W Cairngorms NP

HOW COLD? (AT 900M)

-2 or -3C. Wind chill on higher terrain close to -20C.

So I’m sitting snugly – and smugly – at my kitchen table watching the garden trees whipping about and contemplating nothing more adventurous than a dog walk. But I am wearing-in a pair of spanking new leather winter boots that are warm and strong and quietly reassuring me that together, we’re going to move mountains.

Well that’s a wrap! On the 21st of November we raised our glasses and cheers in a celebration event to mark the end of the Shared Stories: A Year in the Cairngorms project and to launch the anthology of writing that was gathered across the year. Wonderfully, some people travelled from as far as Falkirk, Perth, Aberdeen and even Ayrshire to swell the 70-strong crowd at The Pagoda in Grantown.

As well as wee speeches from Grant Moir, CEO of the Cairngorms National Park Authority, Anna Fleming, project manager, and myself, we had readings from several contributors. These featured commissioned writer Linda Cracknell, poets Karen Hodgson Pryce and Jane Mackenzie, and local crofter Lynn Cassells, whom some of you will know from the BBC programme This Farming Life. A personal delight was to round off the readings with a line-up of Cairngorms Lyrics that included Neil Reid, editor of Mountaineering Scotland magazine, pupils at Kingussie High School and myself.

To break up all the words, we had a couple of sets by the Suie folk musicians and finished the evening on a high with the Gaelic singing and step dancing of Comhlan Luadh Bhàideanach, the Badenoch Waulking Group. Their songs all come from the tradition of Highland and Island women singing together round a table as they rhythmically pound and work the tweed. Comhlan Luadh Bhàideanachhave been together for nearly 25 years and in October won the Harris Tweed Authority trophy at the Royal National Mod. It was brilliant to bring these groups of musicians back into the Shared Stories project again as they had supported our open mic night in the Badenoch Festival in September.

At the end, everyone milled about over drinks and nibbles, grabbed copies of the book and discovered many connections and crossed paths. Scotland is a small place, and never smaller than when landscape and literature meet. Anna Fleming had led the editing and production of the anthology, sourcing the perfect cover art from Steffan Gwyn and overseeing the design to yield a beautiful, high-quality publication of which we’re all very proud. Copies are available in visitor centres, bookshops and libraries across the Park, by donation to The Cairngorms Trust.

And for those who don’t have a copy yet, here’s my introduction to the anthology, which is also a good way of summing up the work of the year. (Don’t worry – this is not my last post and chorus – that’s next week!)

Introduction

It’s a very powerful thing to fall in love. Lynn Cassells, p 77

This book is a story of the heart. It is a collection of writings from very different people with one thing in common: their interactions with the rocky heart of Scotland, the Cairngorms. As you will see, it is what Nan Shepherd called ‘a traffic of love’.

The anthology arises from the 2019 project Shared Stories: A Year in the Cairngorms. Organised and part-funded by the Cairngorms National Park Authority, with additional funding from The Woodland Trust and Creative Scotland, the project set out to encourage people to write creatively about how we and nature thrive together. As the first Writer in Residence for the Park, my role was to facilitate this work through a varied programme of activities taking me all over the bens and glens of the Cairngorms and into the company of countless folk. There were open workshops in three locations, drop-ins at the Cairngorms Nature Big Weekend and Forest Fest, and workshops with schools, rangers, health walk groups, educators, land-based workers, outdoor instructors and Park volunteers. We invited everyone to the table and welcomed every voice.

Throughout the year, rich conversations emerged about people’s experiences of the natural world of the Cairngorms, whether they were born-and-bred locals, settlers or tourists passing through. Inevitably, there are as many perspectives as there are people. There can be controversy and conflicts of interest across the National Park, but the space for shared creative activity enabled us to exchange views with open-ness and interest, rather than argument.

The groups I attended had some really great insights into the landscape, nature and ways of life that I had not seen before. Blair Atholl participant

Most people claim to value nature, to see it as both beautiful and necessary, but most of us have blind spots about the ways in which we threaten it. A key element of the project, therefore, was to address blind spots. Not by exposing ignorance or harmful lifestyles, but by turning the focus the other way and opening our eyes to nature: encouraging us to peer deeply, to pay attention, to discover the complexity and wonder of the world around. We appealed to the senses, going outside wherever possible to tune into the sights, smells, sounds and feelings of a place. Sometimes I spread forest finds across a table – moss, lichen, leaves, stones and branches – and we focused on one small thing. Much like Linda Cracknell in Weaving High Worlds on page 46, people discovered infinite dimensions.

Attending the Shared Stories workshops changed the way I appreciated the Cairngorms. I saw a richness of colour and depth of texture that had previously passed me by. Ballater participant

But more than just discovery, the project invited people to capture their encounters in words. In trying to find the right words, we are forced to pay even closer attention and move beyond assumptions. What exactly is the colour of that sky – here, now? How surprising that this clump of earthy moss smells like medicine, not dirt. And when we make attention a habit – a way of being in the world – we begin to notice how astonishing, how precious and how vulnerable nature is. Alec Finlay in Conspectus, page 16 talks of ‘the power of looking.’ We become aware of what is here, what is lost and what is on the brink. It becomes a gaze of love. And, I hope, of committed action. We will look after what we love.

Thank you for opening our eyes and ears. Kingussie participant

An important thread through Shared Stories has been the celebration of languages. In the workshops, we explored the Gaelic, Scots and Pictish place names of the Cairngorms, along with the rich lexicon of local words for the outdoors. Amanda Thomson’s A Scots Dictionary of Nature was an inspirational source, as you will see from her sixty two words for rainy weather on page 62.

Early in the year, I invented the poetic form the Cairngorms Lyric which proved a dynamic tool for enabling all kinds of people to capture a Cairngorms moment while also enjoying language diversity. Folks were delighted to discover they could write the entire Lyric in their own language and I was delighted in turn to hear many different languages joining the Shared Stories throng. That is why a Spanish Lyric is included in this collection, along with poems in Gaelic and Doric.

Being able to use my own language makes me feel I belong.Abernethy participant

Finally, a fundamental aspect of the project has been the sharing of the stories. This always happened in the workshops, of course, but also spilled out onto eight banners displayed in Visitor Centres across the Park. We held an open mic night as part of the new Badenoch Festival in September, drawing both workshop participants and others to tell their tales. In addition, we encouraged input from anybody, anywhere, who would like to express their Cairngorms nature encounters, and these pieces – from as far afield as the US and Australia – appear on our project blog: sharedstoriescairngorms.tumblr.com It has been exciting, too, to see Shared Stories activities in other contexts, such as RSPB’s Sarah Walker getting Junior Rangers to write Cairngorms Lyrics at Insh Marshes.

For me, it has been a year of gifts. I have learnt so much from my own traffic with this place and its people and have a head humming with experiences, images and words. Some of these have taken shape in my blog about the project, Writing the Way, and others are emerging as poems, but much of it will continue to find voice in the years to come, I am sure. For this store of treasure, I am deeply grateful.

This anthology, therefore, seeks to capture the range of voices and experiences that have responded to Shared Stories: A Year in the Cairngorms. The work here spans young children to a woman in her 80s; academics to farmers; ‘locals’ to visitors. There are works commissioned from four professional authors and anonymous pieces found amongst papers at the end of drop-in workshops; there are poems and prose pieces; serious reflections and comic encounters; enduring memories and luminous visions.

Throughout, these voices express the shared sense that we, in our humanity, are part of nature and integral to this place. In the earth’s thriving, is our own thriving; in the well-being of the Cairngorms environment, is the well-being of its community. As Samantha Walton says in Embodiment, page 22 ‘How rare to be alive to all this’.

We invite you to celebrate with us this shared life – and this shared love – of the Cairngorms.

Photo by Stewart Grant

Though the Glen Tanar Health Walk group love where they walk and were very happy to have me join them, it was made clear that they did not want to do any writing.

I said, ok, I could certainly work on that understanding. In fact, most of my engagement with the Health Walk groups for the Shared Stories project has not involved a ‘writing workshop’ as such. Each group is different and rather than impose an unwelcome activity, I’ve tried to come alongside them and enrich their weekly outing in ways that respond to their interests. My times with the Grantown, Aviemore and Kingussie groups are described here.

My first visit to Glen Tanar was a typically cold, grey and drizzly November day. It’s nearly two hours’ drive for me and burrowing through thick cloud on the rollercoaster Snow Roads, I did wonder if it was worth the time and effort just to trudge along with a group who maybe didn’t really want me there. In the car park of the Glen Tanar Charitable Trust, I watched them emerge from their vehicles adjusting their plumage of waterproof jackets, trousers, gaiters, boots, hats, scarves, gloves and sticks. No outing in the Cairngorms is just ‘a walk in the park’!

But they were brimming with smiles and laughter and greeted me warmly, Glynis offering me chocolates from the bag she passes round every week. I thanked them for including me and assured them there were no writing activities and the last thing I wanted to do was to spoil their walk. More smiles and laughter, maybe even a little relief.

Glen Tanar is on the eastern side of the Cairngorm mountains where the Tanar Water flows into the River Dee. Once the lands of the Marquis of Huntly, the estate was bought in 1865 by Manchester banker and MP, William Cunliffe Brooks. Since 1905, it has been owned by four generations of the Coats family, who now run it as a diverse Highland estate for field sports, holiday accommodation and weddings.

Because of Scotland’s access laws, anyone is free to roam on private land (respecting certain restrictions) and the Charitable Trust actively encourages people to explore and enjoy Glen Tanar, in particular its National Nature Reserve. The Health Walk here has been doing exactly that every Friday, come rain, hail or shine, for many years, usually in the company of a Trust ranger. And it’s easy to see why.

The landscaped gardens were designed for Sir Cunliffe Brooks at the end of the 19th century and include a series of connected ponds and 200 different tree species. Now somewhat overgrown, a creeping wildness is overtaking the Victorian fancy, original paths and flowerbeds lost under the competing tangle of native and introduced plants. On that misty, late Autumn day, the place was breathing its stories, pungent with the cycles of growth and decay.

One lady showed me a giant stump from which 15 new saplings had sprouted, mostly different kinds of tree. We stopped to look at an abandoned summer house, its wood quietly rotting as a fairy-tale stone well stood sentinel nearby. The group pointed out the tendrils of leaves from the very rare twinflower, and at a lochan fringed with reeds, we watched a heron in its perfect stillness.

“Don’t step on the frog!” someone said.

“It’s a toad, it’s a toad!” Ranger Mike was rolling his eyes. The group laughed. Apparently this happens regularly.

“When I was wee,” a senior lady murmured to me, “we just called it a puddock.”

Afterwards we retired to the warmth of The Boat Inn, where the coffee was fragrant and the scones served up like a Bake Off Showstopper. Every Health Walk ends with this gathering for beverages and a blether, and the two halves of the expedition are equally enjoyed. The Glen Tanar group sat around one large table and I asked if they’d like to play Talk in the Park. It’s a simple activity where each person in turn chooses a card, reads out the conversation prompt on it and then shares with the group. Not everyone has to take a card, of course, but as soon as someone starts, most folk want a go and, inevitably, everyone is involved in listening and pitching into the conversation.

One of the cards read: Talk about a person who is a frequent companion in your nature experiences. Aileen’s face creased into smiles, her eyes shining, as she talked about the wonderful person who had gone with her on nearly every outdoor adventure for countless years. “And that’s him, there!” She grinned, pointing across the table at her husband. “Oh that’s a relief,” he said, cheekily. “Was wondering who she was talking about.”

When I gave out a sheet of Scots words for nature, former school teacher Mary launched into a spontaneous and splendid recitation of the fabulous poem The Puddock by John M Caie. Cheers and applause all round and no arguments about whether it was a frog or a toad.

“Now,” I said at the end, passing round the Cairngorms Lyric handout, “I know you folks aren’t interested in the writing, but this is just to show you some of the things that have been happening across the Park. Just for your interest, you know. Just… well, just in case…”

And, as they say in all the best internet click bait, you’ll never believe what happened next.

(But you will have to wait till next week to find out…)

What is your hope for the Cairngorms? It’s a question I put to the audience at a talk I gave last month in Inverness. I was lucky enough to be on the programme of Ness Book Fest, a vibrant and fast-growing literature festival held every October in the Highland capital. Running since 2016, the festival brings together well known and grass-roots writers of all genres in 4 days of free events across the beautiful autumn city. In an ‘Outdoors Double Bill’, I was paired with wildlife photographer Charlie Phillips, most famous for his work with the bottle-nosed dolphins in the Moray Firth.

My talk was titled ‘A Sense of Place’ and was an opportunity to share about my writing and encounters with people and the natural world in one of the most treasured – and controversial – areas of the Highlands: The Cairngorms National Park. I shared some of the many things that make the Cairngorms so remarkable as a home to extra-ordinary wildlife and an equally colourful array of human characters.

I talked about my role as Writer in Residence for the Park this year and how the Shared Stories: A Year in the Cairngorms project has evolved. I read some of my poems, as well as extracts from this blog and my Cairngorms-set novel. (And nobody fell asleep, I promise!)

At the end, I asked the audience to write down their own hopes for the Cairngorms and to leave their slips of paper with me. Here are a selection of the responses:

- that they continue to stride across the land, in all their magnificence

- for the Park to remain a beautiful place where the weather demands respect, where you can walk and hardly meet a soul

- crisp skies, towering peaks, rapid waterways, furry friends, remaining forever

- that it continues to bring joy to all those who live and visit and the wildlife is protected and flourishes

- to see eagles ever flying over the green loch

- to persevere and maintain its beauty through change and adversity

- that people and nature would thrive in harmony with the land which will endure beyond time.

- the mountains to stay accessible to hikers all the time

- to preserve the wild places for people to enjoy and appreciate

- to restore more of the uplands to an ecologically rich environment, while ensuring employment for residents

- regeneration of the landscape

- storytellers bringing the mountains to life in word and poem, linking people to place, honouring wilderness and allowing us to find our home there, even if for a short while.

- that people will experience the wilderness areas – and leave them wild.

- that its beauty is sustained. That it is respected, loved and cherished. That nature will continue to prove stronger than man.

- to endure, to embrace, to keep its heart secure

Reading these responses when I got home was moving. If people care about a place and its wildlife and growing things, then maybe they will work to protect it.

What are your own hopes for the Cairngorms?