Latest

Posted on 11/05/22 in Other, Writing

Chapel of the Swans

On a knoll at the northern end of Loch Insh in Badenoch stands a beautiful little white church with a long history and several names. One is the Chapel of the Swans. I first saw the church when our family were visiting the area and pulled up our canoe on the shore below. We walked all around it, peering through the clear windows before discovering to our delight that the door was open and the interior a haven of peace. The north-east window at the front was graced with an engraved Celtic cross based on St John’s Cross from Iona Abbey. Not long after that visit, we moved to the village of Kincraig, joined the congregation and gradually learned more of its fascinating story.

During the Roman occupation of Britain, the peoples living in this area were the Picts. They were one of the Celtic tribes and had a powerful upper class of priests, known as druids. We don’t know for certain what the Celts believed or what form their religious practice took, but there is evidence of both human sacrifice and the use of hilltops for rituals. It is quite probable that where the church sits today was one of their ceremonial sites. But its name, Tom Eunan, points to a later page in its story. In Gaelic, ‘tom’ means ‘mound’ or ‘hillock’ and Eunan or Eònan is the shorter version of Adamnan, so it means: ‘Adamnan’s Mount’.

But who was Adamnan? Born around 625 in Ireland, he came to Scotland as a monk, ultimately becoming the 9th Abbot of Iona. A man of rare scholarship for his time, he wrote the first biography of Columba, the original founder of the Abbey and credited with establishing Christianity in northern Scotland. Written in Latin a century after Columba’s death, Vita Columbae is considered our most important text from early-medieval Scotland, giving not just a protrait of the saint but also of the Picts and the early Gaelic monks. Adamnan died in 704, was made a saint himself and at some point, the church at Insh was dedicated to him and called St Adamnan’s, or St Eunan’s.

Several of the churches in Badenoch, however, including this one, believe their roots could go right back to Columba and his first disciples in the 6th century. A strong tradition holds that the site of Insh Church is one of the few places in Scotland where Christian worship has been held without break since that time. These founding monks often settled on a place of former pagan worship where they built a small stone cell to live in. They used a clearing beside it for gathering the local people to hear their teaching, summoning them with the ringing of a bell. Inside Insh church, there hangs an ancient hand bell that legend maintains belonged to St Adamnan himself. This is unlikely, however, as most bells of the 7th century were iron and this one is bronze. It is possibly a replica of the original and certainly over a thousand years old.

Whatever it lacks in original metal, however, it makes up for in myth. One story holds that not only did Adamnan use it to call the people, but that he also took it down to the shore of Loch Insh to summon the swans to worship. Sure enough, a very old name for the kirk is the Chapel of the Swans. The bell was also believed to have healing power and because of this – the story goes – was stolen and carried to the Scone Palace, where the Scottish kings were crowned on the Stone of Destiny. From the moment it was snatched from the chapel at Insh, however, the tone of its special ring began to change. With a mournful, homesick tolling, it cried out Tom Eònan, Tom Eònan, and no sooner was it set down in Scone, than the magic bell took to the air and flew all the way home again, wailing the whole way.

Unfortunately, its powers of healing did not extend to itself, for when someone dropped it on the old cobble floor of the church it broke, losing a chip and its voice. Legend has it, that if anyone tries to ring the bell, a curse will befall them and a family member will die within the year. For a time, therefore, it was chained up out of reach to prevent such a tragedy. Now it simply hangs on a bar in an alcove of the church under a brace of flame and flanked by doves. Doves are a symbol of peace and of the Holy Spirit – and the Gaelic name for St Columba, was Colmcille, which means ‘the dove’.

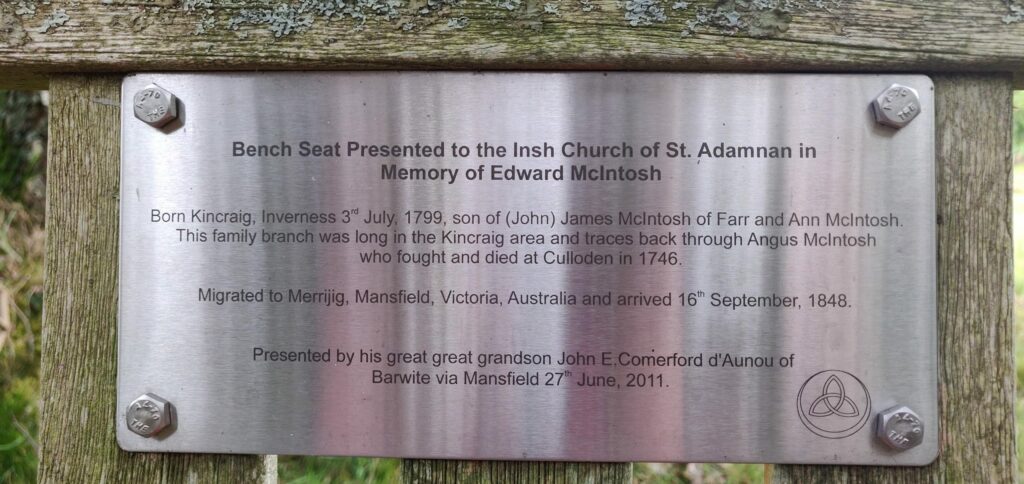

The first written record of the church is in 1190 and the rough stone font in the porch is believed to date from that building. The structure of the building was probably changed several times over the years, but was completely razed and rebuilt in the 1790s as one of the ‘Parliamentary’ churches. Designed by Thomas Telford, these were ordered by the Hanoverian government seeking to suppress Catholic and Jacobean strongholds in the Highlands. The building today dates from then, though significantly remodelled both inside and out.

The old Irish myth of the Swan Children of Lir has also been linked to the church. In the story, the widowed King Lir marries his wicked sister-in-law who is jealous of his four children. Turning them to swans, she banishes them from Ireland, but grants them beautiful voices. They fly across the sea to winter in a faraway land, finding refuge on a loch where they are summoned to worship by a monk’s bell. Loch Insh lays claim to the honour, of course, but not without some basis. Not only do we have Adamnan’s Bell, but this is also one of the chief wintering sites in Scotland of whooper swans. Unlike the mutes, who are here year round, they have a distinctive, mournful cry. You can watch local author and mountain man, Cameron McNeish, tell the whole story here.

Today a Church of Scotland with an active congregation, its common name is Insh Church, Kincraig. It is very special to both locals and visitors, carrying a sense of the sacred in its quiet simplicity. Up until Covid, it was never locked and has always welcomed strangers. One of these, who left his name in the visitors’ book, was John Lennon. Perhaps, for a moment, he imagined there was a heaven.

With its many names and stories, The Chapel of the Swans found its way into my recent novel, Of Stone and Sky, set here in the upper strath of the Spey. Here’s the opening of my chapter Kirk:

It sits on a knoll above the loch, Scots pine rising around it like a company of worshipful giants, waving their arms in the wind, hushing and swishing through the hymns of the sky, leaning quiet to the earth’s prayer. Birch and larch are gathered amongst them, rowan and aspen, oak and yew. A choir of rooks cry out as they beat their silk black robes and circle and roost. Some of the graves in our churchyard are so old the names are lost under lichen, others so new the soil yet lies wounded. To step here is to enter the sacred. It is one of the thin places they say, where the veil between heaven and earth – between spirit and flesh, above and below – is slight as a bee’s wing.

A version of this article first appeared in The Sunday Post. The photographs of me outside and inside the church are by Andrew Cawley. All other photographs are my own.