Millions of people around the world are celebrating Diwali, the Festival of Light, and it always takes me back to South Asia where I was born and brought up. I returned to work in Nepal with my husband in the late 90s and early 2000s and here is a memory from exactly 20 years ago, first published in the Guardian Weekly. Most of the photos in this post are by kind courtesy of Rowan Butler, whose work can be seen on his site Yaksnap.

This is Bhai Tika, the day for worshipping brothers. My own brother, unworshipped, is sprawled on the grass watching his son and mine at play. It is a late autumn evening in Kathmandu, and the air is whispering of snow. The poplars shiver, casting a handful of leaves to the wind.

My niece charges past and shouts, pointing to the north. There – above the valley of houses, above the eyes of Swayambunath temple, above the wooded hills and a parting drift of cloud – are the mountains. They are shining, white and gold and unearthly as if a veil had just been lifted on the plains of heaven.

Bhai Tika is the last day of Tihar, the Nepali festival of light. In India they call it Diwali, and it is one of the most important events in the Hindu calendar. It celebrates the myth of Rama who rescued his wife Sita from the demon king Ravana. When they returned triumphant to their own city of Ayodhya, the people of the city welcomed them with thousands of oil lamps.

So today, Hindus light up their homes, don new clothes and gather with loved ones for days of feasting and ceremony. In Nepal, the emphasis is on the goddess Laxmi. She is the goddess of luck and wealth, her curvaceous form swathed in a bright sari, gold coins pouring from her palms. In one of the poorest countries of the world, maintaining good relations with Laxmi is vital, and her image adorns nearly every home.

In the classically Hindu spirit of all-embracing devotion, worship at Tihar is offered not only to the goddess of wealth, and one’s brothers, but also to crows, cows and the humble dog. The devout leave out offerings of sweets and rice in woven leaf plates for their animal friends, and many a flea-bitten street mongrel can be seen sporting a garland of marigolds and a red splash of powder on its forehead.

It is a time of riotous celebration, with fireworks exploding through the streets, and bands of musicians playing wild tunes. Bedraggled school-children go door to door with a drum and a limited repertoire of songs that they shout, rather than sing, until you pay them to go.

In a recent trend reflecting the rise in western influence here, some of the wealthier teenagers assemble rock bands on the backs of trucks and regale their neighbours with the very latest in Nepali, Hindi and American pop.

This usually decorous society loses its head a bit, as men drink and gamble, and young folk carouse in the streets and throw loud parties. There is, inevitably, excess and brawling, so my doctor husband works nights in the hospital emergency department to patch up the casualties.

But this is a beautiful season. A month after monsoon, the skies are washed clean, the rice has been harvested and the great Himals appear for lingering moments at the rim of the valley. They are like queens emerging on balconies to gaze briefly down on their subjects before gliding back behind curtains of cloud, as if they believed we could not bear the force of their beauty for any longer.

Here in the valley, young boys fly colourful paper kites from roof tops, as women can be seen picking their way gracefully across muddy streets in saris of vermillion, turqouise and parrot green. Scarlet poinsettias splay out against the sky, bougainvillaeas hang heavy with bunches of deep pink, while trumpet lilies echo the white of the distant snows. Everywhere are the brilliant marigolds: in garden beds, balcony flower pots and in garlands draped above doors and around the necks of dogs and brothers.

Tonight, I bid farewell to my brother and his family and take my son home in his pushchair, bumping and bouncing over the ruts. Darkness is gathering softly and the night smells of firecrackers and smoke. A couple of dogs trot beside us as we pass houses where lights are winking on. We turn in at our gate, stepping around the mandala – the geometric design drawn in powder on the ground. From it, a line of red mud leads towards the landlord’s door. The way is lit by flickering oil lamps. It is all to entice Laxmi to visit and bestow prosperity.

The landlord and his sister meet us at our door with warm greetings and a plate of food – lentil cakes and hard-boiled eggs rolled in spicy sauce. I carry these into the kitchen where the curtains are billowing with the cool breeze. My son pulls closer into my arms. I don’t know where Laxmi is tonight, but beauty has swept in and poured her gifts at my feet.

My head is still in the Himalayas. Two weeks ago, I shared about my childhood in Ghachok, a village in the mountains of Nepal which is home to the Gurung people. We left it in 1976, and over the years, have made several trips back. This is the story of those returns.

The first one was in 1984 with my brother’s friends. Not much had changed then except that Mark and I were now tall enough to bang our heads on the door lintel, which felt like the end of childhood.

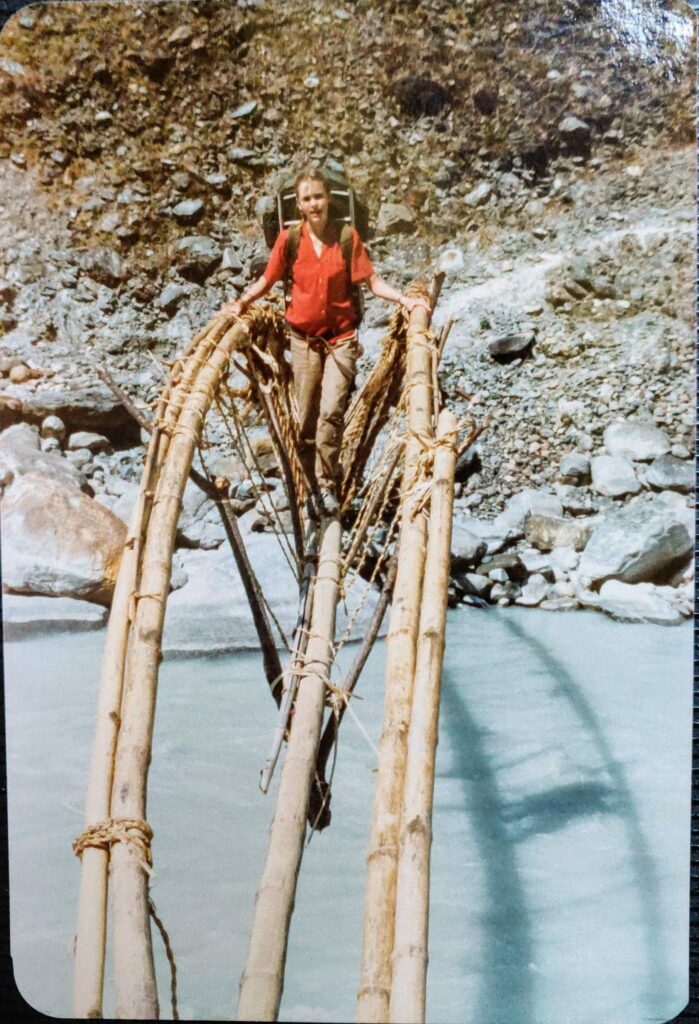

1984 on a familiar bridge

We noted on each of our visits how more of our village friends and neighbours were moving away, often to the town of Pokhara down in the valley, but equally often to places overseas. Many young men were serving the Gurkhas in far flung postings and many of the young women were married to them. On one return to Australia in 1987, we met our landlord’s daughter with her new husband in Singapore. The girl who used to tear round the village in bare feet and wild hair that she wouldn’t let anyone brush, had been transformed into a vision of beauty and grace. That entire family has now left the village.

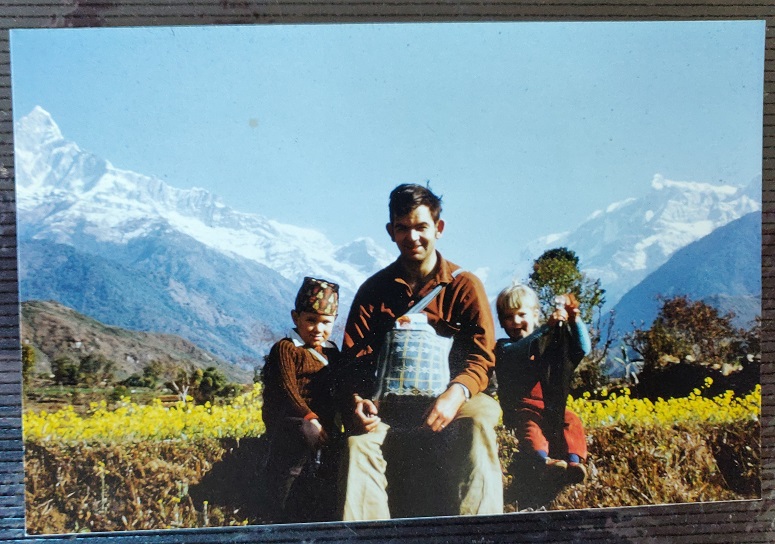

In 1998, we were all working back in Nepal and with our parents, Mark and I took our growing families to see Ghachok: his wife and two wee kids, my husband and our baby, though he was just a tummy bean at the time. Our old house was vacant, so we slept in the musty room upstairs and peered out the back window at Machapuchare. The main difference by then was the establishment of the Annapurna Conservation Area Project and the replacement of goats – whose grazing habits inhibit forest re-growth – with ducks. They were great for curry but not so good for cuddles.

We went again in 2004 to celebrate my parents’ 40th wedding anniversary, with a few more children in tow, though my doctor husband and younger son missed out, as the latter came down with pneumonia. A pony helped the kids up the mountain and my Dad, with dodgy knees, back down. We went with a trekking company who erected tents for us at the edge of the village and it felt dislocated. Electricity poles and wires were marching up the plateau, but even more people had gone.

So when I asked to go again this year, as part of my parents’ farewell from Nepal, they were ambivalent. For our sake they would go, but didn’t expect many meaningful connections. We clocked the first major difference before leaving Pokhara: there is now a road and a regular bus that took us all the way there in 90 minutes, heaving and blasting its horn up the un-metalled track, a few kids piled around the driver for good measure.

The second innovation was the well-appointed Machapuchare Village Inn, where a friend had booked us for the two nights. It had spotless rooms with attached western bathrooms (no Time magazines), solar heated water and mobile reception better than the Highlands of Scotland. We walked above the village to find the springs where we used to picnic, but they were lost under the new forest and the dirt cutting for an extension to the road. There was rubbish underfoot, but overhead, scarlet and golden orioles rippled through the branches.

Some of the terraced fields looked abandoned, while others had been cleared by machine. There was no sign of the traditional ploughman with his yoked cattle, though, interestingly, the goats were back. Perhaps they are allowed now that enough forest has taken hold. Whatever the reason, they proved as adorable and obliging as ever, one even kissing me on the lips.

As we explored the village, to our surprise and delight, more and more of the old guard appeared and welcomed us with excitement: Abhwee! they cried. There was also cheerful critique in the case of my brother. Nepalis dye their hair well into old age and the men don’t grow beards, so Mark’s white designer stubble threw them. “Oh you’ve grown old!” they exclaimed. Or, “You used to look good!” He took it on the chin, so to speak.

As the oldest child, he had been named Surya (pronounced Soordzay) by the community, which means ‘sun’. The rest of the family are simply named in relation to the first-born (male or female): Surya-ma-aaba (father), Surya-ma-aama (mother), Surya-ma-nani (oldest girl). In a culture with close ties across extended families, there are distinct kinship terms covering most relationships: father’s eldest brother’s wife; cousin-sister on the mother’s side; youngest son; even younger youngest son (when a surprise turns up). Although everyone gets an official legal name, it is rarely used in childhood, and means there are multiple ‘nanis’ and ‘tagus’ scampering around the village; it also reflects the importance of the place within the family over the identity of the individual.

Mark was 7 months old when my parents arrived in the village and were given a vacant hovel to rent. Abandoned because it was allegedly haunted, their capacity to survive its maleficence perhaps changed its fortunes, as it has been in use ever since. As a baby, Mark spent many happy hours on a potty out the front waving to passers-by, so we took a commemorative photo on the same spot, though without the full re-enactment.

We returned to a second house where we had stayed (too young for my memory) finding the elderly owners now crippled by stroke. Sitting in their dark kitchen/living/bedroom, with him half-paralysed and her hobbling, we talked as their daughter-in-law made tea over a fire-pit in the earthen floor, a method unchanged in fifty years. Then she went outside and took a video call on her smart phone.

Back at the house where we had spent most of our time, we climbed the wooden log ladder to the verandah that had been school and dispensary. It was covered in corn cobs and the door to our living space was locked. Peering through, I saw the light from the northern window fall into a dusty cavern of corn husks and old bamboo mats. The ceiling was gone and the wooden beams gave way to slated darkness. It was hard to imagine the bright home that had been filled every night with people and the sounds of Gurung chatter, songs and even dancing.

But as we walked the old trails, more and more of those people remembered and found us again. One was Bara Hakim, a man with speech and learning disabilities whose nickname meant ‘Big Boss’ because he very ably commanded all around him. Then there was Goma-ma-aama whose son had been our playmate, and the widow of Purna, the porter who had delivered our mail and supplies. Another was Bobar Singh, the son of our neighbours up the path who had been desperately poor. It was reassuring to see he was dignified and well educated, though, like many, he has no work.

He insisted on guiding us around to Lasti Shon, a waterfall that had been a favourite picnic spot. Although the water is snow melt and icy cold, I have swum there on every visit and this occasion was no different.

Returning via the plateau rim, hundreds of feet above the Seti river gorge, we were stopped in our tracks by the sight of eagles riding the thermals. They took off from the cliffs below and passed us, their vast wingspans just feet away, before rising above, a dozen or more wheeling in the sun.

Another old acquaintance, Baru Kaji, got wind of our visit and insisted we eat at his home on our last night. Like many places in the village, his is now a Home Stay with support from Australian Aid and Australian Caritas. Though most village houses are still traditional with earthen floors and cattle sheds at the side, they now have external brick toilets and a courtyard tap. Many also have satellite dishes. Made entirely of organic produce from Baru Kaji’s own fields, our meal of rice, daal and curries was plentiful and delicious. One thing that hasn’t changed in Ghachok, however, is the wife preparing the food, serving everyone and then eating alone at the end. The position of women in Nepal has improved dramatically in the past fifty years, but they still have multiple challenges (of greater significance than dinner time etiquette.)

Our mornings in the village began with clear skies and the sunrise lighting Machaphuchare behind us. The quiet was touched only by the old familiar sounds of cocks crowing and people’s voices, carried easily on the windless air. And then the bus would arrive, rumbling and blasting its way up the road, under the concrete archway and past the multi-storey, multi-coloured Buddhist gompa. (There were none here even 15 years ago.) But that breach of the peace was nothing against our final night, when Nepali pop music was broadcast across the valley till 5am in celebration of a local wedding. In one bouncy song, a young man tries to woo his girl but discovers the price of love these days includes an iphone and a flight to America. (She’s certainly not eating last!)

One thing remained. On the final morning, standing in the sunshine with Machapuchare behind, I got my family to close their eyes and figure out the object I placed into their hands. It didn’t take too much fumbling and false guesses before they realised it was the old knitted dolls quilt. You can watch the moment here. There was something both gentle and powerful in the coming together of those hands that had made the quilt all those years ago; a family weaving back together in stitch and story.

They say you can’t go home, and we were all aware of the perils of nostalgia and the reality of change. But that journey was far more than a return to the past; it was an affirmation of a family’s life together. It was a difficult life at times and we are no dream family, but it was a life fired by a purpose greater than itself. We were ordinary people in an extraordinary place and I am forever thankful. To be there again together, for the last time, was gift.

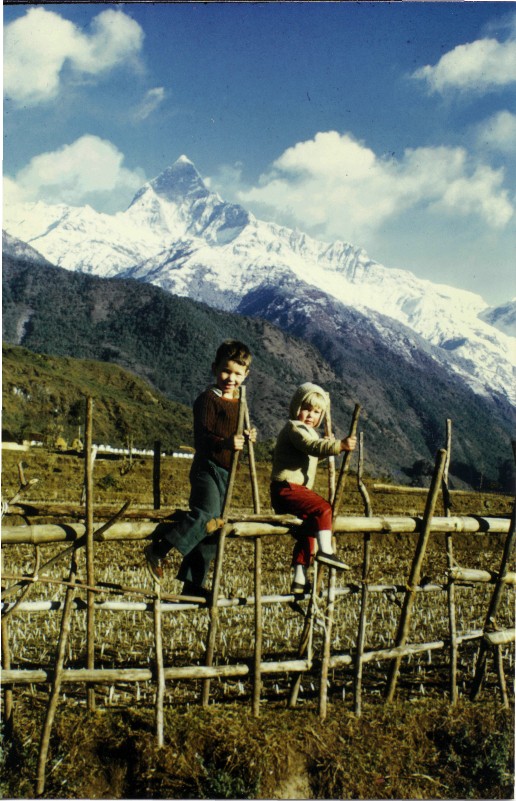

Ghachok village sprawls across a sloping plateau below Machapuchare – Fishtail Mountain – one of the most striking in Nepal. At the centre of the Annapurana range, the peak rises in a sharp triangle that has never been climbed, since a failed attempt in 1957 when it was declared sacred and out of bounds. The mountain stood like a shining guardian over much of my early childhood in the Gurung village that now falls just within the Annapurna Conservation Area Project.

When I was first carried there as a baby in 1969, there was no Project and no road. The walk took four hours and involved crossing the foaming Seti river on a swaying bridge made of three bamboo poles. I was under three when my Dad got me to walk the whole way, requiring multiple rests at tea shops and several extra hours. I don’t remember that occasion, but I do remember many later trips when he kept me and my older brother, Mark, going with stories: Aesop’s fables, Bible tales, the history of Nepal.

My parents were working in linguistics and literacy among the Gurungs, who are one of over 100 ethnic groups in Nepal and one of the four groups that can join the Gurkhas. Their language – which they call Tamukyui – is from the Tibeto-Burman family and had never been written down. My parents worked with them over the years to choose a script and to represent their language in it; the Gurungs chose Devanagari, used for Nepali and Hindi, because they learn it in school.

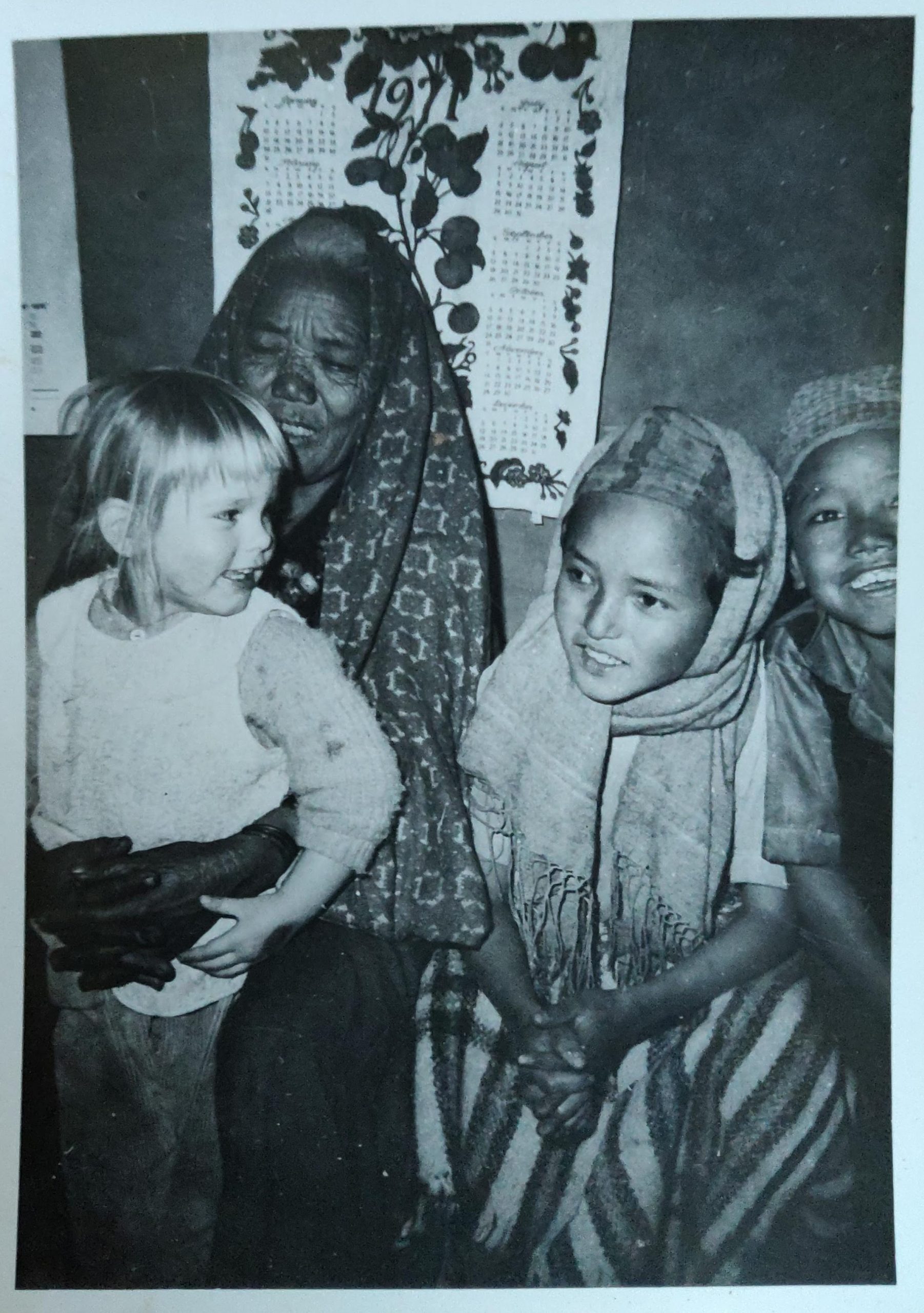

We lived in the village for several months at a stretch over a period of 9 years as my parents learned the language and culture, taking copious recordings and notes. Back then, there was no electricity and all water had to be carried on backs from a source higher up the plateau. We had the only kerosene pressure lamp in the community, which meant our home was packed every night with visitors eager to flick through the National Geographic magazines and the View Master slides. (Congratulations to anyone old enough to remember what that is!)

Our home was the middle floor of a house that the landlord had especially constructed to be high enough for my Dad, but like all village dwellings, had only wooden shutters and no glass in the windows. The buffalos and goats lived on the ground floor below us, while the rats had the penthouse, scuttling among the baskets of grains and corncobs under the slate roof. We had one room divided into sleeping and living areas by a sheet of orange hessian, with a half-panelled lean-to at the end that served as ‘office’. Our ‘bathroom’ was a round plastic basin and the ‘toilet’ was a pit in the neighbouring field, surrounded by bamboo matting. My father’s Time magazines were torn into squares for loo roll, though it was a bit too shiny for the job and made for a frustrating reading experience.

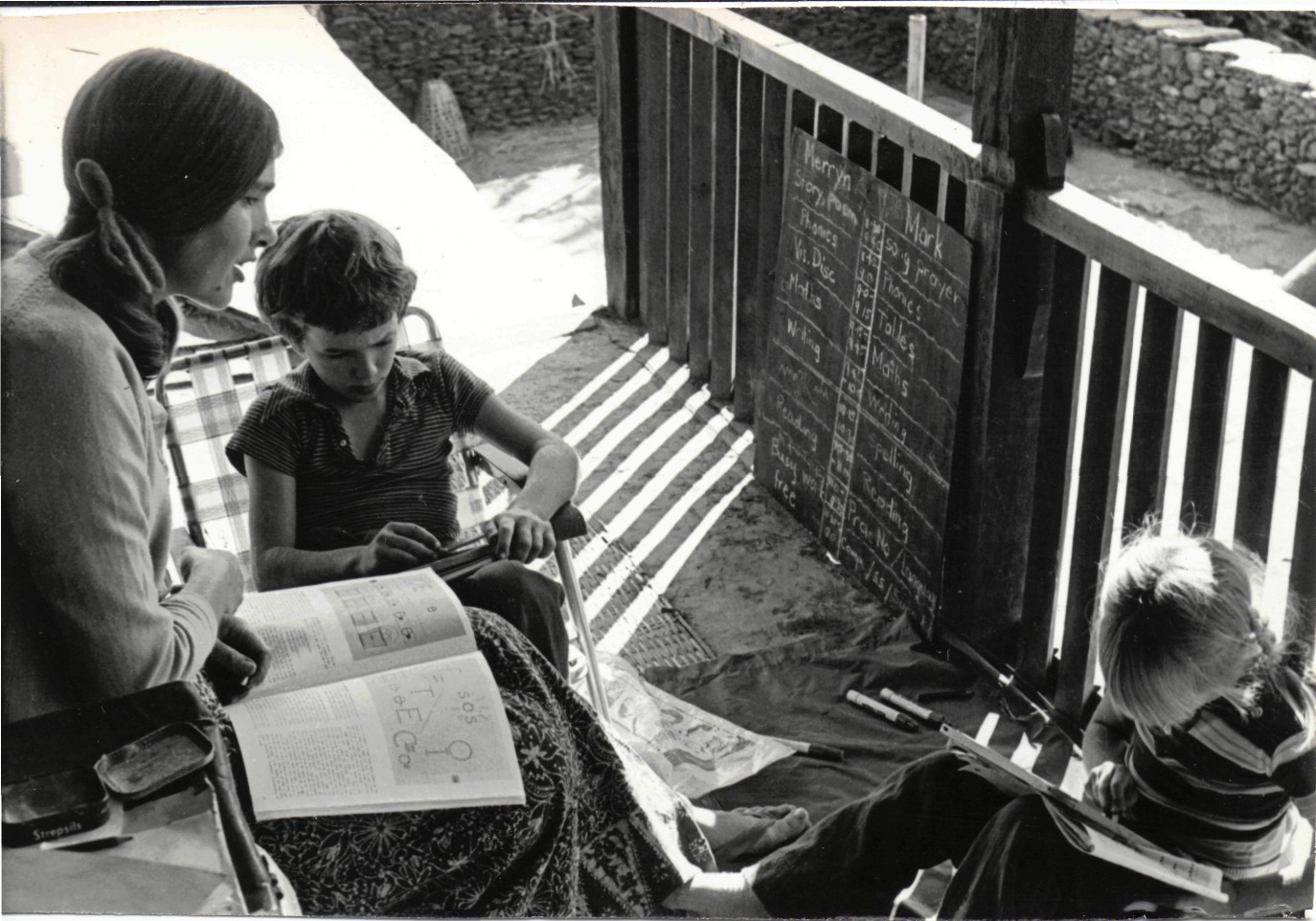

My mother home-schooled us at one end of the front verandah, while a growing number of village folk queued patiently at the other, waiting for her to tend their injuries and ailments. Watching her dispense pills in folded paper packets and daub Gentian Violet on cuts, I always assumed she was a nurse. It was years before I realised she was actually a teacher and relied on the legendary text Where There is No Doctor to help the community and keep us alive.

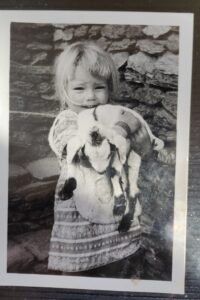

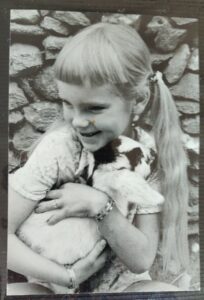

Like other village kids, Mark and I took a turn of perching on the high bamboo fences to scare off the monkeys from the crops and joined the procession to a central field for the slaughter and butchering of a buffalo. The meat was so tough that even pressure-cooking rendered it barely edible. Animals were everywhere, as was their life and death, their ritual sacrifice and place on the menu. I skipped across the stone-paved yard past flustered chickens who turned up in curry a few hours later, chopped into squares with feet and comb included. We always had a cat to ward off the rats, but my favourite animals were the baby goats, who had silky coats and velvet ears and never fought off my cuddles.

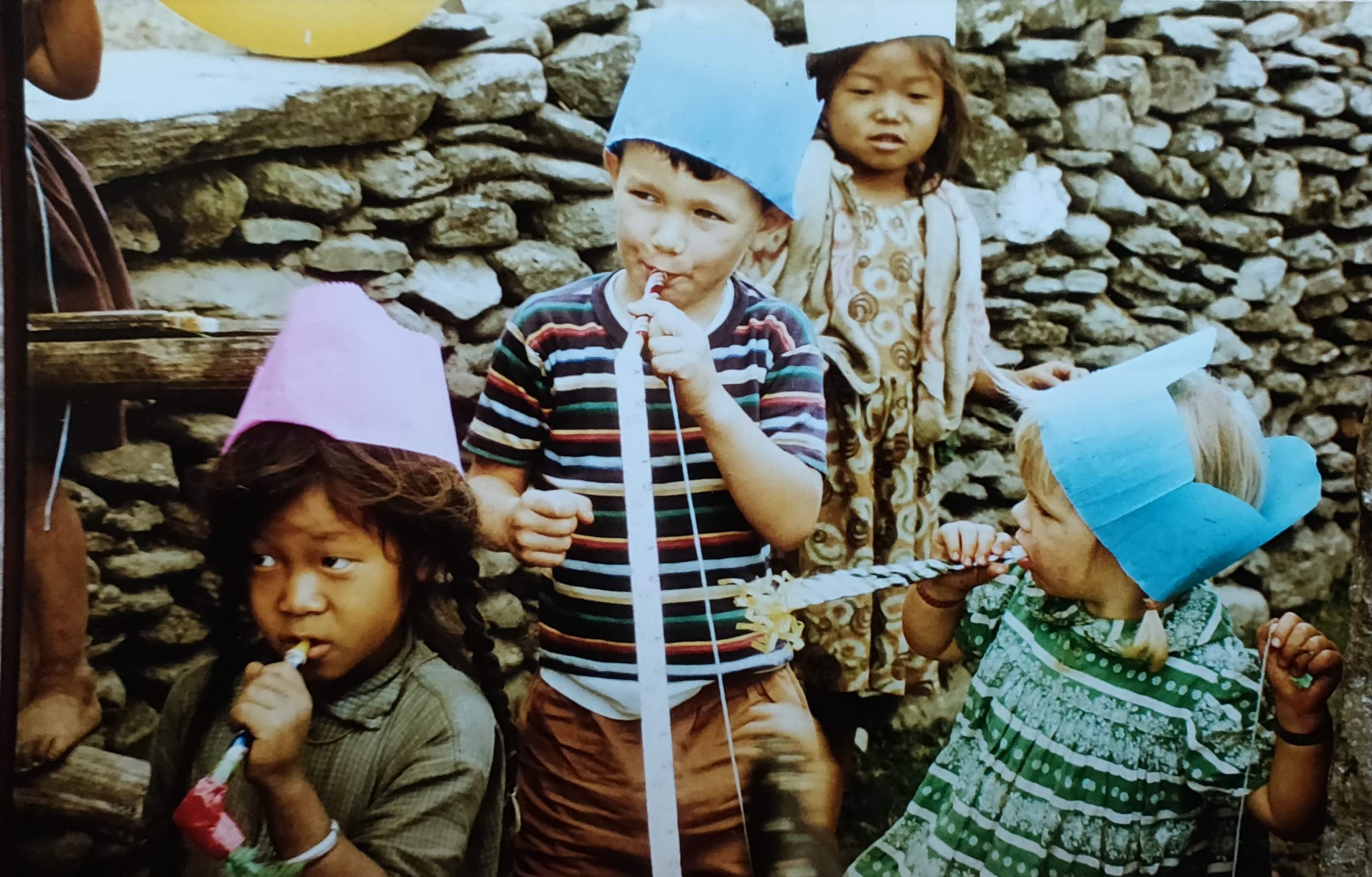

Our school lessons only lasted a few hours each morning and the rest of the time we were free to roam with our village friends. Playtime was often a blend of their games with our toys. Our parents were careful to keep our possessions minimal in the village, but Mark’s trainset was a great hit as was his wooden gun. Long and thrilling hunts ensued, where one kid was the deer and the rest of us galloped off past bamboo clumps and over stream beds in hot pursuit. The finale was to gather the dry stubble from the corn fields and build a small fire, pretending we were roasting and eating the venison.

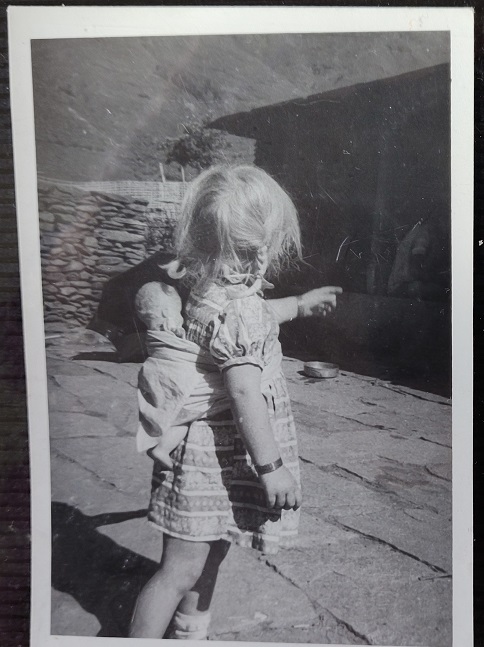

My own treasure was my doll, whom I carried around on my back and laid in a bamboo basket like village babies. I’d slept in one myself, suspended from the rafters above my parents’ bed, where they could give me a swing if I cried in the night. Tragically, I left my doll in the ‘office’ one night and found her the next morning with half her face eaten away by rats. (Heaven knows what the cat was up to.) I was distraught, but loved her all the more fiercely, wrapping scarves over her head and keeping her close. Around that time, my mother taught us to knit and Mark and I produced a series of misshapen squares. Unbeknownst to me, Mum knitted some extras, sewed them together and backed them with flannelette to make a quilt for my doll. It was my Christmas present that year in the village, and though the doll has long since vanished (hopefully to a place without rats), I still have the blanket.

Now 82 and 79, my parents, are finishing up their work with the Gurung project, and when they said it would be their last trip to Nepal, I said I wanted to be there. Mark pitched in eagerly and so it was that last week, the four of us set off for Ghachok. Just before leaving home in Scotland, I pulled out my childhood photo album, snapped some pictures on my phone and tucked the blanket into my bag.

The story of what happened next is in the coming post. See you there!