Setting up a new event is like taking a running jump off a pier. You don’t know if the water’s going to be freezing, or tangled with seaweed or possibly even infested with sharks. But you just have to do it. Even in time of covid when the complications are multiplied and people are afraid. Especially in time of covid.

And so it was that musician Hamish Napier and myself took the plunge with The Storylands Sessions in September. It’s a new series of events in Badenoch, the lesser-known cousin of Strathspey, higher up the legendary river. Meaning ‘the drowned lands’ in Gaelic, this beautiful floodplain between the Cairngorms and the Monadhliaths is a rich source of stories, from Pictish battles to Jacobite strongholds, the Ossian epic to the Wolf of Badenoch.

It has led to a new name for the area, ‘The Storylands’, in a drive to celebrate its unique heritage. But the stories are not just from the past. Like the Spey, they loop and flow on down the generations, changing course and character as successive peoples come and go, adding new voices and making new stories. So the idea for The Storylands Sessions was born. These are two monthly events in Badenoch, one an open mic focused on storytelling and poetry, with music weaving it all together, and the second a trad tunes session, threaded with stories.

The venue for the open mic is the Loch Insh Watersports centre, so I decided our first theme would be ‘water’ and desperately begged everyone I knew to come and, better still, tell a tale. I was terrified only two-and-half people would turn up and it would feel like slowly setting concrete. But I arrived to a room bright and beautifully arranged by the Loch Insh team and a gradual trickle of people with eager faces.

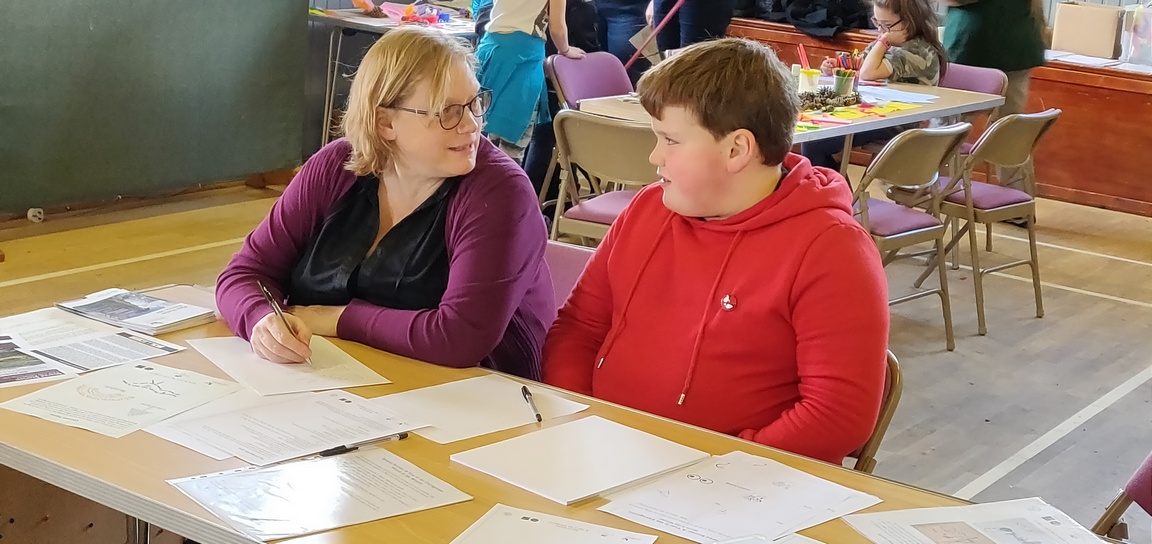

In our Introduction to Storytelling workshop we started by talking about the common sayings and mottos in our families, like “Waste not want not” or “Blood is thicker than water”. And then we asked: who were the natural raconteurs of our upbringing? The repositories of family history and local legend? There are stories all around us and we tell them all the time, from our explanation for being late to the blow-by-blow account of Auntie Yolanda’s disastrous wedding.

After the workshop, Hamish kicked off the open mic with a bright reel on the whistle called Spey in Spate in celebration of this waterway so prone to flooding. We then listened to Duncan Freshwater’s story of his father Clive’s landmark battle to win access rights on the river in the early days of the Loch Insh watersports centre.

Then the night flowed on through poems about eels, the Spey and The Grey Coast; a comic ballad about an old fisherman, a song about boats and more music on piano, guitar and bazouki. There were hot pies and cold drinks and the stories spilled out: the one from Alice Goodridge, our channel swimmer who was ‘billy no mates’ when she arrived here looking for dookin buddies and has gone on to set up Cairngorm Wild Swimmers and Loch Insh Dippers, with hundreds taking the plunge.

I told the story of The Chapel of the Swans, our ancient church above Loch Insh, with its monks, myths and magical bell. We listened to the tale of a runaway canal barge and a woman’s memories of carrying water to her Irish grandmother’s house. The evening finished with the story from Alistair, my husband and a local GP, of the time in Kathmandu when his unconventional use of ‘Water of Life’ – electrolyte solution – saved a woman’s life. Hamish played us out with his original piano piece, The Dance, and by the end, the place was brimming.

People were talking and laughing – masks and space retained where necessary – but still wallowing happily together in the great wash of good company. Afterwards, when we were packed up, I was exhausted, but high as a kid catapulting off a pier.

Two weeks later, we rode the wave again at The Ghillies Rest bar in the Duke of Gordon Hotel, Kingussie. This time Hamish was master of ceremonies for the Trad Tunes night, and his workshop, A Guide to Folk Sessions, was booked out. With guidance on everything from handling beginners’ nerves to arranging jig medleys, it covered the ABCs of making these mysterious, slippery community gigs work.

Once the music struck up, we had fiddles, whistles, guitars, keyboard, bodhran, a banjo, two harps and a set of small pipes. Keeping everybody in tune and time is no mean feat, but Hamish never once resorted to whacking folks with a shinty stick. He’s saving that for next time. Along with a host of eager amateurs, we were lucky to have top local musicians Ilona Kennedy and Charlie McKerron on fiddles and Sandy MacDonell on pipes. There was even a song, with everyone belting out the chorus of Yellow on the Broom. Together, we lifted the roof.

We have longed for this: to come back together and share our stories, our songs and our lives.

The Storylands Sessions are on every first and fourth Tuesday of the month till February 2022 – and hopefully longer. The second Tuesday of the month is the storytelling event at Loch Insh Boathouse, Kincraig. Our next one is October 12th and the theme is Migration – of wildlife, people, ideas, languages or however you wish to interpret it – so come and share your tale, poem or music! We’re very lucky to have Traveller, author and storyteller, Jess Smith, as our special guest, who will be telling stories and leading a workshop at 7pm on The Natural Voice. Advance booking is essential: click here.

Then, the fourth Tuesday of every month is Hamish’s Trad Tunes session at the Duke of Gordon Hotel, Kingussie. Again, the workshops start at 7 and need to be booked in advance, while the sessions start at 8.30 and are drop-in. For full information and bookings see here. If you’re in the area, come on in – there’s a seat for you.

A shorter version of this article first appeared in The Sunday Post.

What happens when we pay close attention to nature? A Sense of Place, about my residency with the Cairngorms National Park, first appeared in the 2020 Summer issue of The Author.

‘Do you see them? There’s a ruby – and over there, a sapphire!’ The senior gentleman points his walking stick into the long, frosted grass where melting droplets are firing with all the colours of the prism. The more we look, the more jewels we see, winking brilliantly in the November sunlight. Later in the pub, they read me their poems.

In stillness by the river, a woman gathers sounds and memories that take her back to a childhood walk and a kind lady’s biscuits. She writes the story for the first time and glows with the telling.

A schoolgirl sits so quietly in the woods that a ladybird roams over her finger and into the words on her page.

These are just some of the encounters that have stayed with me from Shared Stories: A Year in the Cairngorms – my project as the first-ever Writer in Residence for the Cairngorms National Park, which ran throughout 2019. The aim was to encourage participants to express in words how people and nature thrive together.

The relationship between humans and the natural landscape is a key priority for the Cairngorms National Park, which is the biggest national park in the UK and a unique, fragile environment. Half its land has international significance for nature, and it is home to a quarter of the country’s threatened species, including the red squirrel and the elusive capercaillie. At its heart are the Cairngorm mountains, a granite massif of connected summits. They were once higher than the Himalayas, but worn down by glaciers, wind and weather over millions of years, they are now rounded humps that can be climbed in a day and appear deceptively easy. The reality is much harsher. Rising above the mellow straths, the plateau is a small slice of the Arctic, with a climate as dramatic and dangerous as the rock faces that woo climbers from around the world.

Successive generations of those mountaineers have sought to capture their experiences in writing, often with as much determination and passion as their attempts to conquer the rock. Notable Cairngorm writers include W.H. Murray, whose 1947 masterpiece Mountaineering in Scotland was written on toilet paper while a prisoner of war. When the manuscript was destroyed by the Gestapo, he doggedly began it again. The book is testament not only to his love of the mountains, but also to their power – and the power of writing – to elevate him above wartime despair. Describing the summit of Lochnagar, he wrote: ‘Over all hung the breathless hush of evening. One heard it circle the world like a lapping tide, the wave-beat of the sea of beauty… We began to understand, a little less darkly, what it may mean to inherit the earth.’

Another remarkable Cairngorm author and Second World War vet was Sydney Scroggie, who trod on a landmine in the final fortnight of the war and lost half a leg and his eyesight. A hillwalker from boyhood, he said, ‘I can do without my eyes, but I can’t do without my mountains.’ He went on to make 600 ascents with walk companions and wrote the book The Cairngorms Scene and Unseen. Often walking shirtless, his writing bears witness to the intensity of the sensual experience but also the importance to him of the ‘inner experience, something psychological, something poetic.’

While these men were away at war remembering the Cairngorms, a woman was walking them and writing a book that was only published 30 years later and not truly recognised for another 30 after that. Nan Shepherd’s slim volume, The Living Mountain, is unique in adventure literature and far ahead of its time. Just as her goal as a walker was not to summit the mountain, her goal as a writer was not to document the route or its challenges and triumphs. ‘It’s to know its essential nature that I am seeking here,’ she wrote. Her life-time of deep exploration took her across all the Cairngorms’ terrains and weathers at all paces from running to falling asleep. Throughout, she committed to this ‘traffic of love’ with every fibre of her being.

Inspired by all the Cairngorm writers, but particularly in Shepherd’s spirit, I approached the Shared Stories residency as a pilgrimage of discovery. Although one workshop was with the hardy outdoor instructors of Glenmore Lodge, most of our participants were not mountaineers or trying to pit themselves against the Cairngorms. Many were children and several were over 80, so Shepherd’s approach made sense. Never casting herself as a sportswoman, she was an English lecturer at an Aberdeen teacher’s college and, according to her biographer, Charlotte Peacock, always walked in skirts.

That is, of course, until she walked in nothing at all, which was what she did to enter the cold lochs high in the clefts and corries of the range. Because to Shepherd, the aim was full immersion, a whole-body experience of the mountains that called on all her senses, and both seized and superseded her mind. ‘Here then may be lived a life of the senses so pure, so untouched by any mode of apprehension but their own, that the body may be said to think.’

Senses, therefore, were a key starting point for nearly all the Shared Stories workshops. Wherever possible, I took groups outside and we spent time falling still in the natural world, working our way slowly through each sense, scribbling down the words that came. It never ceased to astonish us how much was revealed when we paid that kind of close attention, even in very familiar places. One group who walked regularly beside the River Gynack, stopped with me on a small wooden bridge and with eyes closed, simply listened. We realised that the stream did not have one sound, but many, like an invisible orchestra with a percussion section, bass notes and an ever-shifting melody. Afterwards, a man from the group sent me a poem and this note: ‘Thank you for opening our eyes and ears on the walks.’

Smell is a sense often ignored until it is assailed, so we needed to get in close to notice the subtleties. Clumps of bark covered in moss yielded a surprising medicinal fragrance quite different to the smoky darkness of peat. And though our generalised image of granite might summon shades of grey, looking closely at Cairngorm rock reveals that it is actually pink inside. Even on the grey surface, the patterns of lichen are full of colours: yellows, lime greens and ochres. And though we may be most protective of the sense of taste, sensibly, we opened our mouths to nature, too, in the taste of wild berries and the tingle of snowflakes on the tongue.

Touch, I learned, is something to be explored with far more than our fingers, as Shepherd, Scroggie and Murray testified, all of whom plunged into mountain lochs. In Scotland, especially, where we spend so much time bundled into layers of clothes, it is startling to peel off and allow the water and weather to reach us. But when we do, the experience is arresting, the focus total. And often, the words that arise are equally rewarding.

The process, therefore, of paying attention with our whole bodies proved vital not only to experiencing the world with more clarity, but also to discovering fresh ways of writing about it. Once we move beyond the clichés – the sky is blue, the grass is green – and seek to capture the truth of what is there, we are compelled to find new words. In a workshop for adults with learning difficulties, we stood under a forest canopy and brainstormed all the different words for green in the leaves above. Emerald, jade, turquoise, lemon, sage, olive. Through this tuning of the senses and intensifying of focus, we begin to recognise the dimensions and complexity of the world around us; the wonders that go un-noticed.

The project was undoubtedly successful for the participants and the Park, but what about me? Writing teachers often share that the energy and time of helping others create can drain your own resources and I certainly felt that way at times. I loved the project, but sometimes while participants were dashing off nature writing and saying how joyous it felt, my own well was dry. Over the year, however, deep things happened. I learned habits of stillness and observation; I captured notes, scribbles and fragments; I read the work of other great writers. And I dedicated time to poetry. My usual ground is fiction and drama, and though I’ve always written poems, in off-the-cuff scraps, I had rarely before invested the slow, patient work of crafting. It taught me how difficult it is to write the kind of poetry I really admire, but how much I wanted to. And perhaps that was the most important opportunity for me from the project: to have a year as Learner in Residence.

On May 1st I got this email:

“I am putting together a collection of poems and short prose by children’s authors in Scotland for ebook publication. Titled Stay at Home! Poems and Prose for Children by Authors Living in Scotland – it will help children come to terms with the changes we are experiencing under lockdown… I would like to invite you to make a contribution, and very much hope you will be able to take part.”

The email had been sent by Joan Haig, whom I’ve only ‘met’ on Twitter but whose debut novel Tiger Skin Rug has been winning much praise since its publication earlier this year. It was immediately clear to me that this inspirational project was in the best possible hands as her emails were packed with information, step-by-step timeframes, instructions and spreadsheets. Oh how I love organised people! Even more, though, she was brimming with infectious enthusiasm. The cherry on the cake – or the raspberry, more aptly – was the publisher, Cranachan.

Cranachan is the name of a beloved Scottish dessert made of toasted oatmeal, whipped cream, whisky and raspberries which is often served at Hogmanay or Burns Suppers. It’s also the name of a dynamic independent publisher of children’s books based on the Outer Hebridean island of Lewis, run by the equally dynamic Anne Glennie. With a diverse selection of titles from Barbara Henderson’s historical fiction to Caroline Logan’s fantasy series, it punches far above its weight and, being small, can be nimble. Perfect, then, for a project like this.

Of course I said yes.

The only startling piece of information in Joan’s super-organised email was the plan to launch by the end of May. Gulp. It certainly focused the mind and I jumped right in, looking down the list of potential topics, grouped in three broad categories:

Life in Lockdown The ups and downs of self-isolation.

Everyday Superheroes Celebrating the keyworkers who are helping us through the pandemic.

The World Beyond Our Windows Nature, wildlife, cultures, castles in the sky, stars & space…

Having seriously caught the poetry bug last year in my residency with the National Park, I chose to write a poem on rainbows celebrating our everyday super-heroes.

So how do you write a poem? Like all writing, there will be ideas humming around your head, but the piece only really begins when words hit the page. This time I started by thinking about what we associate with each colour in the rainbow. As ever, Google gives entertaining results and wastes a lot of time. (All essential writer’s ‘research’, of course.) So, there are the obvious things, like green grass and blue sky, but what about the feelings and meanings generated by each colour? Quite serendipitously, I came across an interesting radio 4 programme The Story of Colour that explored different understandings across time and cultures. Fortunately for the children of Scotland, I decided against referencing Newton and Goethe in my poem, though it was a close call. Finally, I pondered which ‘everyday superheroes’ to include and which colour best expressed what they do for us.

After a few drafts, I sent it out to readers for feedback. Two were good friends, both mothers who have worked as early years educators; another was my poetry buddy Karen Hodgson Pryce, who is getting increasing and deserved publishing success and who always improves my work; and the final and crucial readers were my 6 year-old godson Jonathan and his 9 year-old brother, Micah. Their conscientious Mum got them each to read the draft aloud to her and then emailed their responses back to me. Wonderfully, they both enjoyed it and, interestingly, had different levels of understanding around the metaphors, which I felt was age-appropriate.

Having absorbed the feedback and tweaked the poem over a week or so (which can include taking a comma out and putting it back in the next day), I sent it off and got ready for the digital launch. Like half the planet, I’d already discovered and got sort-of accustomed to Zoom during coronavirus, but had never before attended a virtual book launch, far less contributed to one. It was an honour to be asked to read, so I uploaded a rainbow photo as my background, posted launch invites and found clothes that didn’t look like pyjamas.

Thus, on the afternoon of 28th of May 2020 we held the launch of Stay at Home! It was fun to see Joan, Anne and all the other writers popping onto my screen for the pre-launch meeting, everyone waving and calling out hellos. They included Maisie Chan , Alastair Chisolm and Linda Strachan, who has not only written dozens of books for children but also the Writers’ and Artists’ Guide to Writing for Children and YA. Some folk were on Zoom for the first time and there were kids and other house-mates wandering past or talking from the side-lines. A wee boy asked if he could eat the whole brownie and I’ve no idea what his Mum wanted, but the rest of us said yes.

Once ‘attendees’ were with us (invisible and muted, alas), we had a welcome from Joan, readings and Q&A. It was fitting to kick off with Chief Chebe’s hilarious story Abiba’s Zoom and interesting to hear from illustrator Darren Gate, whose cover captures all the creativity and love holding families together behind lockdown. Look out for the tiny mouse and the gorilla on the bicycle inside the book, too!

But just as everyone was having a fabulous time, our call got cut off. (My moment of poetry fame so cruelly wrenched from me!) After a few frantic texts to and fro, the contributors re-assembled an hour later to record the second-half, although we had, of course, lost our audience. Fear not, the whole thing is stitched together and posted on the Cranachan YouTube channel. (I’m at 35:10. Thanks for asking.)

Finally, there is a wonderful section at the back of the book called Your Turn packed with ideas for children to do their own creative writing in response to the pandemic. It includes prompts like Lockdown for Dummies and Nessie on the Loose. Teachers and home-schooling parents, this gold.

Everyone involved in Stay at Home! has donated their time and skills, so the book is completely FREE. You can find it here to download and read on any device. Do please spread the word so it can be used and enjoyed as a gift from children’s writers in Scotland to kids all over the world.

Finally, you might be wondering why I got invited. Snap. I can only hope it wasn’t a terrible mistake but that some little bird told the organisers I have written a novel for children which is currently out on submission. Anyway, thanks to Stay at Home! I can now definitely say I am a published children’s writer.

Here, then, is Rainbows. Wherever you are and whatever lockdown has meant for you and your loved ones, I do hope these words touch you.

Rainbows

Red is for rosy apples and warm winter gloves

for carers working everywhere with hearts full of love.

Orange is for oranges, bright as the rising sun

for teachers making videos so learning can be fun.

Yellow is for buttercups, bananas and busy bees

for bin lorries passing by and budgies eating cheese.

Green is for gardens and finches in the hedge,

for farmers and food workers bringing healthy veg.

Blue is for rivers and the tears of our goodbyes,

for doctors, nurses, cleaners and all angels in disguise.

Indigo is for evenings and bedtime stories told

with families who treasure us and teddies to hold.

Violet is for dreaming from the cloud-boat of your bed,

going on great adventures in the worlds inside your head.

Rainbows are bright colours held together in one rope;

light in stormy weather, rainbows are for hope.

It’s the Cairngorms Nature at Home Big 10 Days! This WAS going to be the Cairngorms Nature Big Weekend and I WAS going to be over with the rangers in The Cabrach in Morayshire leading a family story-making session. Hopefully, all of that can still happen next year, but in the meantime the folks at Cairngorms Nature have organised a fantastic programme of virtual events from 15th to 24th May. That means people all around the world can enjoy this exceptional place while staying safely at home.

To mark the event, I’m sharing a nature poem each day on Instagram and Twitter. The ten together make up a series called The High Tongue, printed below, which were my contribution to our Shared Stories anthology last year. Exploring the names of ten of the Cairngorm mountains, each title begins with the anglicised version, followed by the Gaelic spelling (if different) and then the translation, which is explored in the rest of the poem. They are all Cairngorms Lyrics. This is a new poetic form I invented last year as Writer in Residence for the Park and you can read all about it here. (For pronunciation of the Gaelic names, look out for a recording I’ll post soon of me reading them all.)

Ben MacDuie – Beinn MacDuibh The Mountain of the Son of Duff High King of Thunder Old Grey Man Chief of the Range Head of the Clan Cairn Gorm – An Càrn Gorm The Blue Mountain Rainbow height: blaeberry bog brown red deer snow white blackbird dog violet moss green bright

Carn Ealer - Carn an Fhidhleir Mountain of the Fiddler She plays the rock with the bow of the wind for the stars to dance Cairn Toul – Càrn an t-Sabhail The Barn Shaped Mountain Storehouse of stone Boulders shouldering like beasts in this dark byre Hail drumming the watershed

Ben Vuirich – Beinn a’ Bhùirich Mountain of the Roaring Once the haunt of wolves howling at night now just their ghosts in failing light Coire an t-Sneachda – Coirie an t-Sneachdaidh Corrie of the Snow Bowl of white light black rock wind run ice hold hollow of the mountain’s hand

Beinn a’ Bhuird The Mountain of the Table Giants gather in clouds of black for a bite and a blether, bit of craic. Ben A’an – Beinn Athfhinn Mountain of the River A’an in a cleft of silence hidden loch secret river name breathed out like a sigh

Braeriach – Am Bràigh Riabhach

The Brindled Upland

freckled speckled wind rippled

shape shifting fallen sky

dark light shadow bright

land up high

Am Monadh Ruadh

The Red Mountains

Range of russet hills

forged in fire at first sunrise

old rust rock

glowing still

It’s the Cairngorms Nature at Home Big 10 Days! This WAS going to be the Cairngorms Nature Big Weekend and I WAS going to be over with the rangers in The Cabrach in Morayshire leading a family story-making session. Hopefully, all of that can still happen next year, but in the meantime the folks at Cairngorms Nature have organised a fantastic programme of virtual events from 15th to 24th May. That means people all around the world can enjoy this exceptional place while staying safely at home.

To mark the event, I’m sharing a nature poem each day on Instagram and Twitter. The ten together make up a series called The High Tongue, printed below, which were my contribution to our Shared Stories anthology last year. Exploring the names of ten of the Cairngorm mountains, each title begins with the anglicised version, followed by the Gaelic spelling (if different) and then the translation, which is explored in the rest of the poem. They are all Cairngorms Lyrics. This is a new poetic form I invented last year as Writer in Residence for the Park and you can read all about it here. (For pronunciation of the Gaelic names, look out for a recording I’ll post soon of me reading them all.)

Ben MacDuie – Beinn MacDuibh The Mountain of the Son of Duff High King of Thunder Old Grey Man Chief of the Range Head of the Clan Cairn Gorm – An Càrn Gorm The Blue Mountain Rainbow height: blaeberry bog brown red deer snow white blackbird dog violet moss green bright

Carn Ealer - Carn an Fhidhleir Mountain of the Fiddler She plays the rock with the bow of the wind for the stars to dance Cairn Toul – Càrn an t-Sabhail The Barn Shaped Mountain Storehouse of stone Boulders shouldering like beasts in this dark byre Hail drumming the watershed

Ben Vuirich – Beinn a’ Bhùirich Mountain of the Roaring Once the haunt of wolves howling at night now just their ghosts in failing light Coire an t-Sneachda – Coirie an t-Sneachdaidh Corrie of the Snow Bowl of white light black rock wind run ice hold hollow of the mountain’s hand

Beinn a’ Bhuird The Mountain of the Table Giants gather in clouds of black for a bite and a blether, bit of craic. Ben A’an – Beinn Athfhinn Mountain of the River A’an in a cleft of silence hidden loch secret river name breathed out like a sigh

Braeriach – Am Bràigh Riabhach

The Brindled Upland

freckled speckled wind rippled

shape shifting fallen sky

dark light shadow bright

land up high

Am Monadh Ruadh

The Red Mountains

Range of russet hills

forged in fire at first sunrise

old rust rock

glowing still

Last week I described my first outing with the Health Walk Group in Glen Tanar. As Writer in Residence for the Cairngorms National Park, I’ve had the pleasure of working with many kinds of people of all ages right across this vast and varied landscape. Some of them have eagerly signed up to attend a writing workshop; others, like school classes, are just lumbered with me. (Though with sometimes surprising results.) And then there are the folk like the Glen Tanar ones, who already have a deep and joyous relationship with their natural environment and no need to write about it. They did, however, graciously welcome me to come along.

My walk with them the first week was cloaked in mist and the swirling stories of the Glen’s history – natural and human. We shared delight in the place and one another’s company, both outdoors and in the warmth of the Boat Inn; and though we didn’t write anything down, the conversations were rich. It’s always been an important principle of the project that we encourage responses to the Cairngorms environment in both spoken and written form. As a local friend observed to me, talking rapturously about this landscape in which he grew up, “I don’t write, Merryn, but I can talk for Scotland!”

Talking is definitely welcome. Which is why I was very happy at the end of my first meeting with the Glen Tanar group. Even though they’d been clear they didn’t want to write, they had been generous in sharing their stories of this beautiful place. I was very much looking forward to seeing them the following week.

I’d barely got home, however, when an email dropped into my inbox from one of the group: Anna. Using several Scots nature words, she’d crafted a Cairngorms Lyric!

Glen Tanar walked in muggle

Autumn 🍂 colours, heron.

Injured puddock walked safely to linky edge.

muggle = drizzling rain; puddock = frog; linky = flat & grassy

I was delighted. Then the next day, another email arrived from Margaret:

“Thanks for joining us on the walk yesterday. I really enjoyed the session afterwards at The Boat Inn.

I’ve always loved reading but have never felt the urge to write for pleasure. However, as we were walking round the loch I felt that I should, perhaps, make the effort to come up with something short and simple and produced this.

Yellow, gold, rust and brown

Autumn’s leaves drift down, heralding Winter’s chill.

This morning, I decided to have a go at a Cairngorms Lyric. This is the result.

Like a sentinel, tall and still,

the silent heron waits by the lochan’s glassy waters.

I’ve just looked online and found that an old Scots name for the heron is “Lang Sandy” so another version could be:

Like a sentinel, tall and still,

Lang Sandy waits silently by the lochan’s glassy waters.

I doubt I’ll set the heather on fire with these but I’ve enjoyed doing it. Feel free to discard or share as you see fit.”

Let me tell, you, these beautiful offerings definitely set my heather on fire! I couldn’t stop grinning – and definitely couldn’t wait to get back to them all. “What are you like?” I said, as we gathered in the car park the next Friday. “The group that doesn’t want to write sends me wonderful poems straight away!” We all laughed.

Our walk that day, this time with Ranger Eric, was bathed in autumn sun, every leaf and frosted twig shining. As we went, we stopped at different points to focus on one sense at a time, smelling the earthy leaf mould underfoot and listening to the rushing Tanar and the high piping of birds. At an old bridge, we pulled off our gloves to explore the textures around us: rusting metal, granite, tree bark, slick wet ice, moss that is normally spongy but now frozen hard as rock.

At the high point of the trail where the view opens towards Mount Keen, we stood in brilliant light, taking in all we could see. Fragile drifts of mist rose from the dark forests, echoing the strands of cloud in the sky, where the blue shifted from intense on the horizon to pale above.

“Look!” said Donald, pointing with his stick. All around us, the long grasses were rimed with sparkling frost, and on each blade, droplets of melting ice glowed like jewels. “See the colours!” He said. And it was true, the longer we looked, the more we noticed flashes of rainbow hues as tiny beads of water caught the sun. “There’s a red one!” someone cried. “Oh look at the brightness of that green!”

When we stop to pay attention, there is no end to the world’s miracles.

Back at the Boat Inn, Anna and Margaret succumbed to my persuasion and shared their poems, to great appreciation from the group. And then – wonder of wonders! – Aileen pulled a scrap of paper from her pocket and confessed she’d scribbled some Cairngorms Lyrics, too. (And for those who don’t know Doric, the translation is below.)

It’s nae the pine I’ll min’

Bit the flash o’ the dipper in the burn.

(It’s not the pine I’ll remember

But the flash of the dipper in the stream.)

I kent the mannie fa’s grannie

planted the linden tree.

That’s foo aul’ I am.

(I knew the man whose grannie

planted the linden tree.

That’s how old I am.)

Well, as you can imagine, I was thrilled. The non-writers of Glen Tanar had penned some beautiful poems and, I’ll wager, were as surprised and delighted as I was. Long may they wander, wonder and – now and again – even write.

Hooray! It’s National Poetry Day today!

For my five years at Kingussie High School library, this was always one of the highlights of my year, when we had poetry readings at lunchtime with drinks and biscuits. There was always a heart-thrilling mix of poems, including in other languages and, last year, in song.

National Poetry Day is a wonderful, country-wide celebration of poems classic and contemporary; a chance to return to an old favourite and discover new gems; an encouragement to sharpen your pencil and have a go yourself.

If that sounds too difficult and you’re struggling for ideas, why not try a Cairngorms Lyric? They’re only 15 words long and even if you’ve never been to this beautiful part of Scotland, you can still write one. If you do, please share it with the hashtag #CairngormsLyric and let’s see how many we can have ringing round the internet!

Here’s one of mine, the first of a series of ten called Calling the Mountains which I will read at Ness Book Fest tomorrow (Friday 4th October) and will be published in our Shared Stories: A Year in the Cairngorms anthology coming out in November:

Ben MacDuie – Beinn MacDuibh

The Mountain of the Son of Duff

High King of Thunder

Old Grey Man

Chief of the Range

Head of the Clan

Another fun and non-threatening way of coming up with poetry is to do it with others. I don’t believe poems are meant to be solitary pursuits; they grow out of our lives together and are shared back into the world. They can also be created in community.

One of my workshops for the Shared Stories: A Year in the Cairngorms project was with the tremendous folks who volunteer across the Park as Health Walk leaders. In the morning we followed HighLife Highland ranger, Saranne Bish, around Anagach woods, where she told us so many fascinating things about the forest and sent us seeking out all its colours. Here’s a wee video of it made by Sian Jamieson from the Park team: Anagach Walk

In the afternoon, I led a workshop on how Health Walk groups might explore different creative responses through words, whether investigating place names, using Talk Cards or writing. One activity was to get everyone to complete the sentence ‘On today’s walk…’ on a post-it note. I gathered these in, arranged them in an appealing order and – voila – a Group Poem was born! Reading it out to everyone at the end of the workshop brought surprise and delight at how easy it was to create and how rewarding to hear.

On Today’s Walk

Group Poem created at Cairngorms National Park Health Walk Leaders’ Training Day

11th September 2019

On today’s walk

we met, we talked, we stopped, we observed

life on a dead tree

On today’s walk

we chatted with new people

we stopped a few times to look around

the sun shone

and the wind blew the cobwebs away!

On today’s walk

we looked at the spectrum of colours

the chatter flowed

the senses were stirred

On today’s walk

we collected a range of scraps

of colour in nature,

looked at lichen

through a magnifier

we sensed the soft decay of autumn

we found the mushrooms for tea

On today’s walk

there was no rain

the invisible snail left a clue

a visible, silvery trail

On today’s walk

we did talk, talk, talk

Why not try it with your own group, whether on a family holiday, with work colleagues (see here for how CEO Grant Moir did something very creative for the Park staff away-day) or in a club or hobby group? Whatever you do, please take a moment on National Poetry Day to stop for a moment and savour a poem – reading or writing. Use the comments below to tell me your all-time favourites!

Namaste!

Most of you probably recognise the word, some of you use it in yoga classes and some may even know what it means. Pronounced num–ah-steh it is the commonest greeting across the Hindu world, usually with palms pressed together, and serves as both hello and goodbye. It’s been part of my vocabulary from childhood as I was born in Kathmandu and grew up in South Asia, so I love hearing it whenever I go back to my beloved Himalayan countries, and I use it as the sign-off for my newsletters. I was amused, therefore, to discover it recently in this Cairngorms Lyric from a workshop participant:

The wind blows, the trees move,

A bird swoops upwards gracefully,

SPLAT! Wind turbine.

Namaste!

One of the three rules of this new poetic form, arising from the Shared Stories project, is that at least one word must be of non-English origin. A very intelligent teenager in a workshop I was leading for Moniack Mhor Young Writers, rightly pointed out that most of the English language has developed from other sources. So it has, and remains all-embracing in continuing to absorb words from everywhere including street slang, tech and the constantly evolving vocabularies of popular use. And that’s the point. If people use them, words inevitably become part of the language.

Despite what English teachers, Scrabble players and other pedants (I’m all three) might insist about what is or isn’t a ‘real word’ or ‘proper English’, there is no legal boundary. Even the Oxford English Dictionary doesn’t own the language; it merely seeks to record it. We do have a thing called ‘Standard English’ and it’s useful for people to learn, as it’s the medium of much information and power, but all the other forms of this vast, sprawling, boundless tongue are not incorrect or inferior, just variations on a constantly changing theme.

But that vastness is part of the problem. English is a great river into which all the words of the world can run, but it also threatens to flood them, to dilute the richness of other languages and to drown them out altogether. Language loss is happening at an alarming rate across the globe. I say alarming because language is a profoundly important expression of culture, and to erase language is to erase a people’s distinct voice and with it, much of their history, literature, song, beliefs and practices. Increasingly, diverse ethnic groups are being absorbed into ever-dominant and homogenised cultural monoliths, and quite often, language is the driver.

Sometimes, this is because ethnic groups rightly recognise their need of the national and/or English language in order to access education, work and influence, and without it they are disadvantaged. At other times, national policies have enforced use of the state language and punished use of indigenous languages and dialects, as happened with Gaelic in Scotland. For both these reasons and more, English is increasingly dominant world-wide, and though I support everyone’s right to learn it to meet their needs, I am also passionate about reinforcing linguistic diversity.

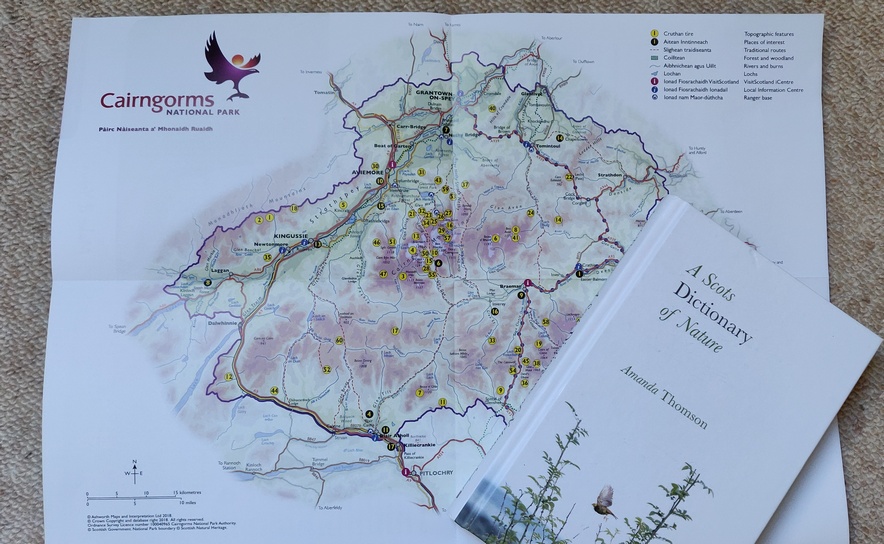

That is the reason I was very keen from the outset of the Shared Stories project that we encourage the use of other languages. This includes the heritage languages of Scotland – Gaelic and Scots – but also all the others spoken by residents and visitors in the Cairngorms National Park. One of the activities I run in schools involves looking at Gaelic, Scots and even Pictish words for landscape and nature, as explored in the Place Names of the National Park leaflet and map, and several books including Amanda Thomson’s wonderful compilation A Scot’s Dictionary of Nature.

And that is why the Cairngorms Lyric must have at least one non-English word. That’s not difficult. Just mentioning a loch or Ben Macdui or a ‘wee’ bird will do it. But many people have enjoyed digging deeper and drawing from the rich meanings of the place names and old words. Loch Mallachie means The Loch of the Curse; Càrn an Tuirc is the Mountain of the Wild Boar. Other people, wonderfully, have included words from other mother-tongues or languages they know. Sometimes, as in the namaste above, they are just a single word. A Welsh boy delighted in having his own country’s greeting in the middle of his lyric:

My feet squelched through wet mud

“Bore da!”

I cried to the squirrels and birds.

- Eoin Jones

But the rules of the Cairngorms Lyric mean the entire thing can be written in another language. When I said this at the workshops I led for school groups at the Rural Skills Day on Monday, faces lit up. Two Polish teens wrote poems that were a mystery to me but had them rolling with laughter; another teen wrote in her native Spanish, which impressed her pals no end; another teamed with a friend to work on the English version together and then she wrote the Polish, which her friend copied down. I loved the way these responses not only reinforced the young person’s use of their language but brought celebration and respect from their peers.

Then in the beautiful Abernethy woods on Wednesday night I led a workshop with teachers and other practitioners for the wonderfully named OWLS: Outdoor and Woodland Learning Scotland. One participant spoke of how Gaelic words for colours were so much more expressive to her. Another read her Lyric in French, filling our forest glade with sounds that, even if we didn’t understand them, were beautiful. “We don’t understand what the birdsong means,” I commented, “but we still enjoy it.” A Danish participant spoke of how glad she was the project embraced other languages and it led to a discussion of the rich potential of drawing from all the languages in the classroom and the many extensions activities such as audio recordings and learning about translation.

And so I invite, I encourage, I urge YOU to join in the project, in your own tongue, and to share the richness of your language and voice with all of us. Come along to a workshop or send us your writing about the nature of the Cairngorms to share on our website and our end-of-year anthology. We want to hear you!

Namaste!

One of my great hopes for this year as Writer in Residence at the Cairngorms National Park was to dedicate more time to my poetry. What time? What poetry? Maybe I was the only person surprised to discover that the role (and writing about it in this blog and other publications) has kept me so busy that there has been little time to wander lonely as a cloud penning verse. This may be of public benefit, but even if my poetry proves of no value to anyone else, I dearly wanted to develop my practice.

And that’s the key word. Practice. Because every time I sit down to write a poem these days what emerges doesn’t sound anything like a poem. It sounds like drivel. Or doggerel. Or doggy-do (to which I have dedicated an entire blog post, should you wish to escape now before accidentally treading in one of my poems.) Perhaps I should stick to expounding the Dog Fouling Act but my soul was rather hoping for higher things.

Hoping, I’ve discovered, doesn’t write poetry. Practice does. I did know that (after all, I preach it at every writing workshop I ever lead). But I also know it because I used to do it. Regularly. I have notebooks, folders and computer files full of poems since childhood, written on everything from napkins to the back of refund vouchers when I worked at a department store checkout as an 18 year-old. (Much more passion than practice at that stage.)

But two things have happened: one is that I have fallen out of practice. The time demands and sheer slog of writing three novels, four plays and numerous stories in the past ten years has only left crumbs under the table for poetry. But the second thing is not committing to the process of re-writing. Most of my poems are dashed off, first-draft impressions – like an artist’s sketch or the hum of an early tune – and while some hold promise, most need work. And there’s the rub. Work is hard. It’s not as much fun as that initial glimmer, that tumble of words scribbled in a notebook.

So, feeling this year of residency galloping by without much poetry from me, I’ve committed to practice. Yesterday, while sitting by the Spey leading a Shared Stories workshop with pupils from Kingussie High School, I wrote alongside them, trying to capture words for the sand martins zinging low across the river. Back home I fished out a description of watching birds at Loch Insh from a few days before, because martins were there, too. And then I flipped back through other scraps and scribbles from my many visits to the Loch, and started to work on those words. What follows here is the series of short poems that emerged. They represent just one evening of effort, so I don’t know if they are finished (how does one know?) and I don’t even know if they are separate poems or a whole, but I do know that crafting them has fired again my love of writing poetry and my determination to practice. (And it’s lifted my soul above that dog dirt, too.)

Loch Insh Birds

a mallard glides through the rushes

velvet green head, pearl white throat

stately as a royal boat

martins zig and zag

zooming, skimming, whipping round

up and down with zipping sound

the osprey strides the air

beating wings against wind

gaining ground, winning the dare

a phalanx of oystercatchers

in perfect formation flight

Red Arrows in black and white

somewhere, a hidden curlew cries

bubbling, whistling, lonely prayer

rising to the skies

Staff away days can be notorious for press-ganging resistant folk through ‘team-building’ exercises like tying Betty from accounts to intern Joey’s back and asking them to leap-frog across the Director in a muddy ditch. Or, just when they’re all filthy and furious, getting them to role-play conflict resolution while onlookers keep score. You might have endured one yourself. Or even organised it. But have you ever been at one that involved writing poetry? The thought may be more excruciating for you than any number of Tough Mudders or office pantos, but hats off to Grant Moir, CEO of the Cairngorms National Park Authority, for giving it a go:

“After reading Merryn’s blog and trying my hand at a Cairngorms Lyric via twitter I thought it would be great to get all the staff at the CNPA to do one. We met for an all staff away day at Glenmore Lodge on the 3rd April which was practically the only snowy day of the year. As an icebreaker (quite literally) I asked all the staff to write in 10mins a Cairngorms Lyric. The rules were explained and everyone really got into it. The results really show the absolute love that folk have for the cairngorms, the nature, wildlife and culture. It was great to do something a bit different.”

Grant then dropped me a note: “Merryn, I have 58 Cairngorms Lyrics from staff! If you could judge the best one that would be great. I am donating a bottle of whisky or gin to the winner.” To be fair, he had asked me first and I was delighted to agree and even more so when I read through the poems. What an astonishing collection of images, emotions and personalities shone through those short pieces, and what a magical way to get a feel for the big and varied team that make up the Park staff.

The genesis and rules of The Cairngorms Lyric are explained here, but in essence, it is a new poetic form invented for the Shared Stories: A Year in the Cairngorms project and is made up of:

– 15 words

– an element of nature

– at least one non-English word

Reading all 58 poems was a dream, but trying to judge a winner was a nightmare! I spread them out on my living room floor, re-read and re-arranged them several times, left them there for several days and dragooned my husband into reading the short-list (a marital team-building exercise). I was struck by several things. One was how powerfully many of the Lyrics expressed the sense of the Cairngorms as home, as in Charlotte Milburn’s above and the one below.

Hame

Crawling up the A9

Brown turns to hazy hues of purple

Cairngorms…

I am hame!

Kate Christie

Several participants took the opportunity to express more political views about the environment, but the issues are sensitive, so I can’t print them here. There were several that enjoyed the opportunity for humour, and some couldn’t resist a little dig at the process:

Snow is falling on Glenmore Lodge.

It’s cold and wet.

Is that it yet?

*Slange.

*Slange or sláinte is Gaelic for ‘health’ or ‘cheers’. Perhaps that writer would have preferred leapfrog. Or something else entirely:

Snow is blanc, squirrels are red.

How I wish I was

at home in bed.

I loved the number of pieces that captured a strong, fresh sense of the natural world:

The osprey in a stramash of water and feathers as it landed the fresh salmon.

Donald Ross

Battle scarred, bleak hills

slowly greening, growing, gathering

a cloak of wild on the woods – healing.

Emma Rawling

If I’m not careful I could end up typing out all 58 of the CNPA Cairngorms Lyrics, because I enjoyed them all so much, but I will settle now for sharing my favourites. This one perfectly captured a Scottish mountain-top experience familiar to so many of us.

Coorying behind a cairn

Cold wind hurtling

Eyes squinting

Lashes filtering snow

Grimace, Brace, Go…

Nancy Chambers

I loved the riddle in the following Lyric and the memory of happy summers with my own kids. Can you guess what it’s about?

Hunters

Guddling about, searching, hunting.

Concentration, competition, down on hunkers.

Satisfaction, blue tongues and lips.

Harvest.

Emma Stewart

Finally, the winning poem stood out for me right from the beginning and stayed at the top of my carpet line-up for the three days. It is reminiscent of haiku in the vivid image of the opening line and the ‘cut’ in the middle that suddenly broadens the perspective: a fleeting moment of bright birds in their antics is set against the ancient time of the wood. Wow. A breath-taking Cairngorms Lyric.

Redpolls and siskins upside down in the birkin branches;

In the forest many lifetimes deep.

Carolyn Robertson

Why not have a go at writing a Cairngorms Lyric yourself? If you do, send it in to us for possible publication on the CNPA website or our end-of-year anthology. Click here for how to do that.